The Tyranny of the Five-Letter Cage: Why Wordle Dominates Our Collective Brain Space

Seriously, look at this data dump—titles screaming about hints for January 5th, 2026, #1661, while the actual, tangible world burns or builds, who knows, because everyone is staring at green, yellow, and gray squares. This isn’t gaming; this is a mass hypnosis event disguised as casual fun, and frankly, it’s hilarious how easily we’ve been played into this daily ritual of linguistic self-flagellation. The sheer volume of search traffic dedicated to finding out the answer to something designed to take three minutes illustrates a profound, almost beautiful laziness gripping the Western (and increasingly, the global) consciousness; we’d rather outsource our trivial cognitive load than actually think, even when the stakes are literally zero, which is what makes the whole spectacle so utterly compelling for someone like me watching from the peanut gallery, ready to mock the proceedings with the zeal of a carnival barker selling snake oil.

The Illusion of Achievement in the Post-Truth Era

Remember when puzzles required effort? When they took up space in your Sunday paper, requiring coffee, maybe even a spouse’s input, leading to genuine, albeit minor, satisfaction? Now? Now we demand spoilers for yesterday’s puzzle (#1660) and hints for tomorrow’s, all while the feed is clogged with people pretending that knowing the word ‘SCRAPE’ or whatever banal collection of vowels and consonants they churned out is some kind of intellectual victory. It’s not. It’s the participation trophy of the digital age, polished up nicely and delivered right to your phone screen before your first actual important task of the day. The dependency is staggering. If the servers went down tomorrow, half the office parks in Silicon Valley would experience an existential crisis far worse than any actual economic downturn, because their baseline distraction mechanism would vanish.

It’s all about the dopamine drip, isn’t it? That little burst when the third letter flips green. It’s chemically engineered micro-dosing. Forget heroin; the new highly addictive substance is the confirmation that your initial, slightly wild guess of ‘ADIEU’ or ‘CRANE’ was utterly, wonderfully wrong, forcing you back into the grindstone of letter selection, all while real life screams for attention outside the glowing rectangle. Think about the collective intellectual horsepower wasted on trying to distinguish between synonyms for ‘dust’ or ‘shine’ when we could be solving fusion energy or, perhaps more practically, figuring out why rent keeps doubling every fiscal quarter. We choose the easy win, the guaranteed small reward, over the hard slog of actual progress, and that’s the real scandal here, the quiet capitulation of ambition under the weight of accessible, frictionless entertainment.

Wordle as a Metaphor for Modern Information Consumption

This game isn’t just a game; it’s a perfect, miniature model of how we process all news, all data, all reality now. We want the headline, the summary, maybe the three bullet points, and if we can’t get the answer immediately, we search for spoilers, thereby removing the entire point of the exercise, proving that the act of searching for the solution is sometimes more important than the solution itself—a terrifying concept when applied to politics or climate change, but perfectly encapsulated by the Wordle hive mind seeking that January 5th key.

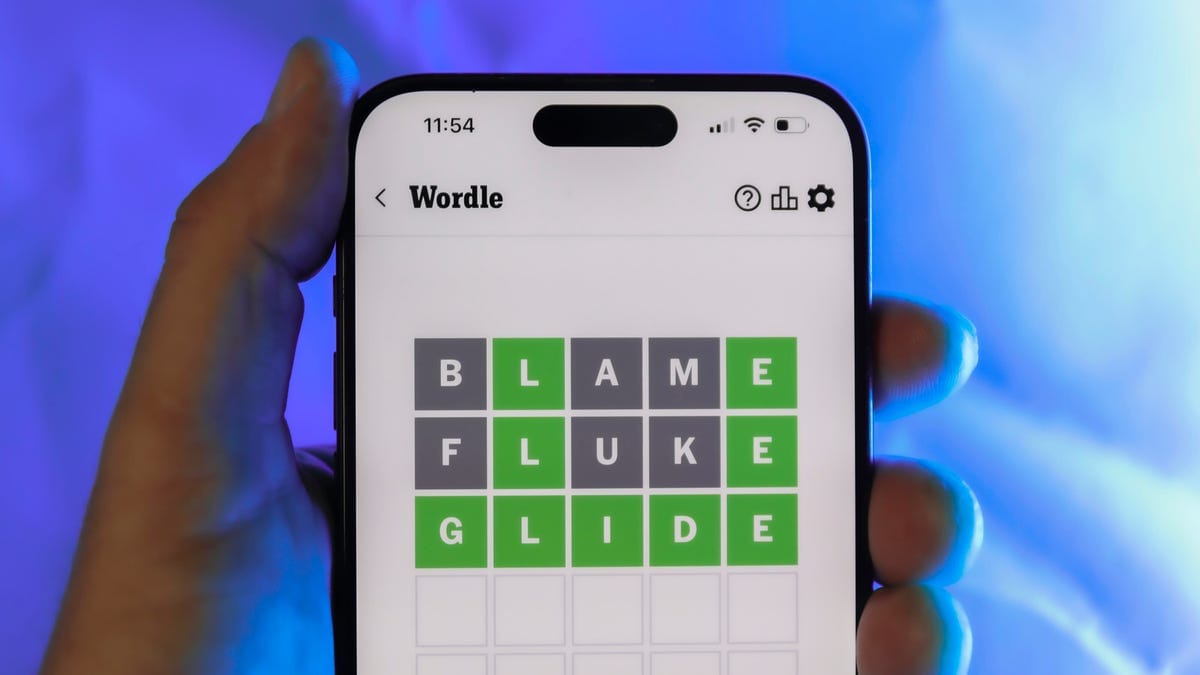

It’s the ultimate low-stakes commitment device. You commit to opening the app. You commit to looking at the grid. You commit to the social signaling that comes from posting your little colored grid on social media, showing everyone, ‘See? I am moderately competent at guessing common English words today!’ This performance of competence is crucial. It’s the grease in the wheels of social anxiety. If you don’t post your score, did you even solve it? The answer, for many, is a resounding no, because the validation, the *proof* of the micro-achievement, must be broadcast to the algorithm that feeds us more reasons to ignore reality.

We used to have water cooler talk about the rain or the stock market; now we have mandated, coded discussions about ‘how many tries it took,’ creating a bizarre, forced intimacy based on shared, pointless labor. The hints for January 4th (#1660) are already archived, meaning the collective memory span is shrinking, already forgetting yesterday’s victory to obsess over today’s impending necessity. This acceleration is unsustainable; we are burning through our daily allotment of novelty at an alarming rate, treating linguistic puzzles like critical infrastructure. What happens when something *actually* breaks, and everyone is too busy checking if the word was ‘CLAW’ or ‘FLUSH’ to notice the lights going out for good?

This obsession transcends mere diversion; it’s a cultural litmus test for cognitive surrender. The fact that New York Times feels the need to publish entire explainer guides, complete with warnings about spoilers for puzzles that expire in 24 hours, tells you everything you need to know about the attention economy; if people are searching for hints for the *day before*, the system is broken, relying on users to clean up their digital messes rather than simply accepting the fleeting nature of the challenge. It’s like demanding the receipt for a forgotten sandwich you ate last Tuesday. Utter madness.

The Economics of Zero-Value Information

Let’s talk money, because everything eventually rolls back to the pathetic pursuit of capital, even digital doodles. Who profits from this desperate scramble for the answer to #1661? The Times, naturally, trading on the intellectual insecurity of millions. They monetize our need to feel connected, smart, and current, all for the price of a subscription that grants us access to this glorious five-letter vortex. The hints themselves are bait—a teaser to keep you clicking on the adjacent, equally time-wasting content like the Mini Crossword or the Connections games, which are just sequels designed to keep the dopamine pipeline flowing, ensuring maximum stickiness. This isn’t entertainment; it’s digital amber trapping our free will.

Consider the time sink. If one million people spend five minutes actively trying to solve Wordle (not counting the time spent looking up hints or complaining about the difficulty), that’s 5 million minutes—over 83,000 hours—gone. Per day! That’s enough collective time to read 8,000 books or perform complex manual labor for weeks. But no, we’re busy analyzing vowel placement because the digital overlords demand it. We are living in the Age of the Trivial Pursuit, where the most important thing you accomplish all day is correctly identifying a word that will be utterly forgotten by midnight, making way for the next mandatory linguistic trial.

The warnings about spoilers are the funniest part of the whole circus. “WARNING: THERE ARE WORDLE SPOILERS AHEAD!” Spoilers for what? A word chosen randomly from a pre-selected, finite list? It’s the media treating a moderately interesting distraction like it’s the final scene of a prestige HBO drama. This self-importance is toxic. We are inflating the significance of our minor daily rituals until they obscure the major societal shifts happening around us, treating linguistic parlor tricks as genuine intellectual engagement. It’s escapism wrapped in the guise of mental exercise, and we are gobbling it up like cheap candy.

The Future: Wordle Derivatives and Cognitive Atrophy

Where does this trajectory lead? Deeper immersion, of course. We’re already seeing derivatives: sports editions, geography editions, perhaps soon, existential dread editions where the answer is always ‘DEATH’ or ‘DEBT.’ The core mechanic is too simple, too scalable, and too addictive to be left alone. We will see competitive leagues, national Wordle championships where the stakes are far too high for the skill involved, and people who dedicate their entire LinkedIn profiles to being ‘Master Wordle Strategists.’ It’s a race to the bottom of cognitive effort, cheered on by the media that profits from our distraction.

Furthermore, the reliance on hints and answers (as evidenced by the search queries themselves) shows a fundamental misunderstanding of learning. True learning involves struggle, error, and reflection. This process is about pattern recognition applied to a limited, artificial set of data, immediately followed by the relief of having the answer handed over. It trains us to expect immediate gratification and external validation for minimal effort, which is terrible training for navigating complex, ambiguous, real-world problems that rarely resolve themselves in five turns. This is why complex problems seem so intractable; we’ve trained our brains on the neat little boxes of Wordle, where the solution is always knowable and finite, and reality refuses to play along, which is why everyone logs back in the next day, hoping for an easier set of letters.

What about the sheer volume of content generated around the *hints*? This indicates a parasitic ecosystem feeding off the main game. People aren’t just playing; they are generating data about how to play better, consuming analysis about yesterday’s failure, and reading warnings about tomorrow’s potential success. It’s a full-time job pretending to play a five-minute game. This manufactured complexity surrounding simplicity is the hallmark of late-stage digital capitalism—make the input tiny, but make the surrounding noise about that input deafeningly loud, ensuring maximum engagement time without requiring any actual investment of self. It’s brilliant, sickening, and utterly predictable. We are trapped in the grid, and we are begging for the keys to the next cell. Pathetic. Utterly pathetic.

What happens when the New York Times decides to make the game genuinely hard, say, by introducing six-letter words or removing vowels entirely? The outcry would be biblical. The hints market would crash. People would realize they weren’t good at Wordle; they were just good at guessing based on the current difficulty curve, which is entirely curated. This manufactured ease keeps the masses docile and engaged, ticking the box marked ‘Mental Stimulation’ while they ignore the actual intellectual stimulation required to function as an engaged citizen in a functional democracy. The hints for January 5th, 2026, are just breadcrumbs leading us away from the actual banquet of critical thought we should be consuming. Don’t fall for it. Or do. I really don’t care, as long as I get a laugh watching the spectacle unfold.

Brilliant.

Unbelievable.

Mass delusion.