Q: Why did President Trump feel the need to wear a pin explicitly contradicting his own self-professed emotional state—namely, the claim that he is ‘never happy or satisfied’?

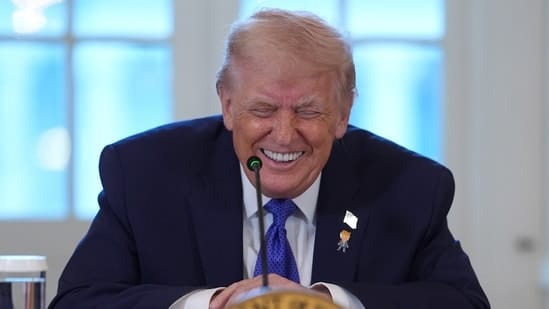

Let’s just cut the rope right here and now: this isn’t about sartorial flair or a funny little trinket; it is about the calculated, deeply cynical engineering of political symbolism, a performance designed to manage the very real gap between the perpetual victim narrative he champions and the required optics of successful leadership, which demands a kind of functional, if aggressive, buoyancy. The ‘Happy Trump’ pin, or ‘Bobblehead Trump’ pin, whatever moniker you prefer for this piece of plasticized vanity, is not a simple gift received—it is a carefully deployed tool of visual communication, acting as a buffer against the endless, aggressive dissatisfaction that fuels his base and, frankly, defines his administration, allowing him to claim perpetual grievance while simultaneously flashing a cartoonish signal that everything is, actually, awesome (or at least, awesome *enough* to warrant a smiling miniature depiction of himself). This manufactured moment, premiering during a critical discussion about the geopolitical powder keg that is Venezuela, wasn’t an accident, it was a distraction missile fired at point-blank range to shift the conversation’s emotional core away from the heavy reality of sanctions and regime change and towards the simple, digestible spectacle of the leader himself.

It’s pure stagecraft. A dodge.

Q: What does this performative symbolism tell us about the current state of political branding in the digital age?

What we are witnessing is the absolute pinnacle of the commodification of personality over policy, where the leader becomes less of a head of state and more of a walking, talking, highly valuable IP—intellectual property, folks, the whole kit and caboodle—where every single item associated with that figure, down to a nickel-plated pin, becomes a piece of profitable merchandise, an identity marker for the consumer-voter who desperately needs to signal allegiance in the most immediate, low-effort way possible (you know, instead of, say, reading policy white papers). This pin isn’t just selling ‘happy’; it’s selling the *idea* that even the most powerful, most famously disgruntled man on the planet can be reduced to a grinning bobblehead, thereby making him accessible, relatable, and perhaps most importantly, sellable to those clamoring for a piece of the action—which, if you look at the reports that supporters were instantly asking, “Where can I get one,” shows that the marketing strategy landed like a lead balloon filled with gold dust.

This is cult branding 101 (and a disturbing evolution from the staid, almost boring symbolism of previous eras, like the simple American flag pin worn by most presidents, which signaled abstract patriotism rather than specific, personalized emotionality).

The Deep Disconnect: Satisfaction and Power

Let’s deconstruct the core contradiction: The man states, quite clearly, that he is “never happy or satisfied.” In the psychological landscape of power projection, this perpetual dissatisfaction is usually spun as a positive—the tireless worker, the relentless negotiator, the man who always demands better, who won’t settle for the status quo (a politically effective stance that resonates with people who feel profoundly unsatisfied themselves). But this approach has an inherent liability: it risks projecting instability or chronic unhappiness onto the national mood, which is why the visual counterbalance—the smiling pin—must be introduced, offering a cognitive escape hatch that allows supporters to believe in the aggressive policy stance without having to absorb the leader’s personal, stated misery. It’s a masterful piece of visual manipulation, asserting, ‘Yes, I am angry and demanding, but look! I also possess this small, easily digestible token of conventional, smiling joy,’ essentially giving the audience permission to cheer the aggression while absolving him of the emotional cost, a strategy that would have been baffling only a few decades ago when politicians were expected to maintain a steady, measured emotional equilibrium; now, the measured emotional state is only achievable through external, commercialized props.

It’s exhausting.

Q: How does this specific incident relate to the geopolitical context of the Venezuela discussion, and the broader ‘America First’ policy framework?

The staging is paramount: You are discussing severe sanctions and potential military action against a sovereign nation (Venezuela), a profoundly serious subject requiring gravity and diplomatic sobriety, and yet, the leader introduces an element of visual farce. What this does is diminish the seriousness of the policy discussion itself; it transforms a complex international crisis into a footnote beneath the spectacle of the leader’s latest accessory, signaling to both domestic audiences and international rivals that the American presidency, at least in this moment, operates on the level of reality television—where the dramatic effect of the prop outweighs the material consequence of the policy being discussed (imagine Franklin D. Roosevelt wearing a ‘Grinning FDR’ pin while discussing the invasion of Normandy, it’s an absurd concept, but here we are in the 21st century, with optics dictating reality). The ‘never satisfied’ mandate is perfectly applied to foreign policy, driving the constant need to challenge existing alliances (NATO), withdraw from agreements (Paris Accord), or challenge regional stability (Venezuela, the previous Greenland acquisition idea), all of which stem from the premise that the status quo is inherently rigged or unfair to America.

The pin acts as the soft cushion for the hard power, a visual whisper saying, ‘Don’t worry, even though I’m tearing up global norms, I’m secretly fun and lovable,’ a profoundly dangerous message when dealing with adversaries who might interpret such visual flippancy as weakness or lack of commitment. You can’t negotiate with tyrants while wearing a cartoon version of yourself unless you intend for the negotiation itself to be perceived as inherently unserious, something akin to a childish game being played on a stage much too grand for it, leading to inevitable miscalculations on the world stage because key players simply stop taking the stated seriousness of the administration at face value, which is a massive diplomatic failure waiting to happen.

The pin matters.

The History of Political Props and the Future of Governance

We need to pump the brakes and consider the lineage of these props. Historically, political figures use props to signal specific virtues or loyalties: Lincoln’s hat, JFK’s youthful vigor, Reagan’s cowboy persona, but the props were generally organic extensions of an existing personal mythos or were neutral symbols of office (the flag, the seal). The ‘Happy Pin’ is something entirely different; it is self-referential, reducing the complex identity of a politician into a single, commercialized emotional state. It’s the ultimate self-parody employed defensively. What does this predict for the future of political engagement? It suggests an ever-increasing demand for personalization and immediate emotional connection, where future candidates won’t just run on platforms but on patented, branded emotional accessories.

We’re moving toward a system where authenticity is not required; only plausible deniability is, allowing the politician to adopt and discard emotional signals like they change ties, which fundamentally destabilizes the trust between the governed and the governor (a bedrock of functional democracy, people!). Imagine the next presidential campaign: candidates unveiling their own line of bespoke, mood-altering accessories, perhaps a ‘Skeptical Sam’ fedora or a ‘Furious Fiona’ scarf, making the political process indistinguishable from a fan convention. This commodification path leads only one place: deeper into the realm of spectacle and farther away from responsible, complex governance, transforming the highest office into a mere promotional platform for whatever identity happens to be selling best that quarter (and, trust me, this is a trend that is not slowing down; it’s accelerating at warp speed).

The bobblehead version of the leader—a figure who nods perpetually without ever having to engage critically—is perhaps the most perfect, depressing metaphor for modern politics that a cynical observer could hope to invent; the fact that the actual leader adopted it into his formal attire is simply breathtaking in its self-awareness, or rather, its total lack thereof, depending on how you look at the whole shebang. The supporters, asking ‘Where can I get one,’ are not just buying a pin; they are buying into the performance, cementing their place as consumers of the political brand rather than participants in the political process, a deeply worrying development because a democracy fueled by consumer impulse is one that is always a hair’s breadth away from collapse, ready to trade long-term stability for short-term emotional gratification.

It’s pure, unadulterated political junk food, highly addictive and utterly devoid of nutritional substance. And they are lining up to consume every last bite.

It’s the end of seriousness.

This relentless pursuit of personal branding, often achieved by leveraging cheap, mass-produced merchandise, fundamentally cheapens the office and the institutions it represents, making it nearly impossible for serious policy discussions to retain their gravity in the public consciousness—when a key meeting about international stability is overshadowed by the provenance of a lapel pin, we have crossed a threshold from serious governance into perpetual, low-grade vaudeville, and the world is watching, calculating the depth of the abyss. This isn’t just a political trend; it’s a structural decay, folks. Pay attention.

We should also consider that the ‘Happy Pin’ provides an instant, easy visual rebuttal against the constant media characterization that the administration is chaotic or perpetually angry, a simple, non-verbal rejoinder that sidesteps the necessity of engaging with complex criticisms, which is precisely why it works so well on Fox News Channel (where the pin was likely noted extensively during shows like ‘Special Report with Bret Baier’ and ‘The Ingraham Angle’ mentioned in the source material, reinforcing the visual narrative of the happy, successful leader, regardless of the verbal content being delivered).

The real implications of the pin lie not in its appearance, but in what it proves about the current political ecosystem: that surface-level affirmation, the quick hit of visual conformity, is vastly more powerful than deep, complex policy reality, meaning that anyone in the future who seeks power must be prepared to fully embrace the bobblehead aesthetic—the constant, slightly manic grinning in the face of immense, global responsibility—or face being deemed ‘unhappy’ and therefore, tragically, unsatisfying to the modern consumer of news and politics.