The Great Climate Mirage: Why Phoenix’s Christmas Rain Is No Cause for Celebration

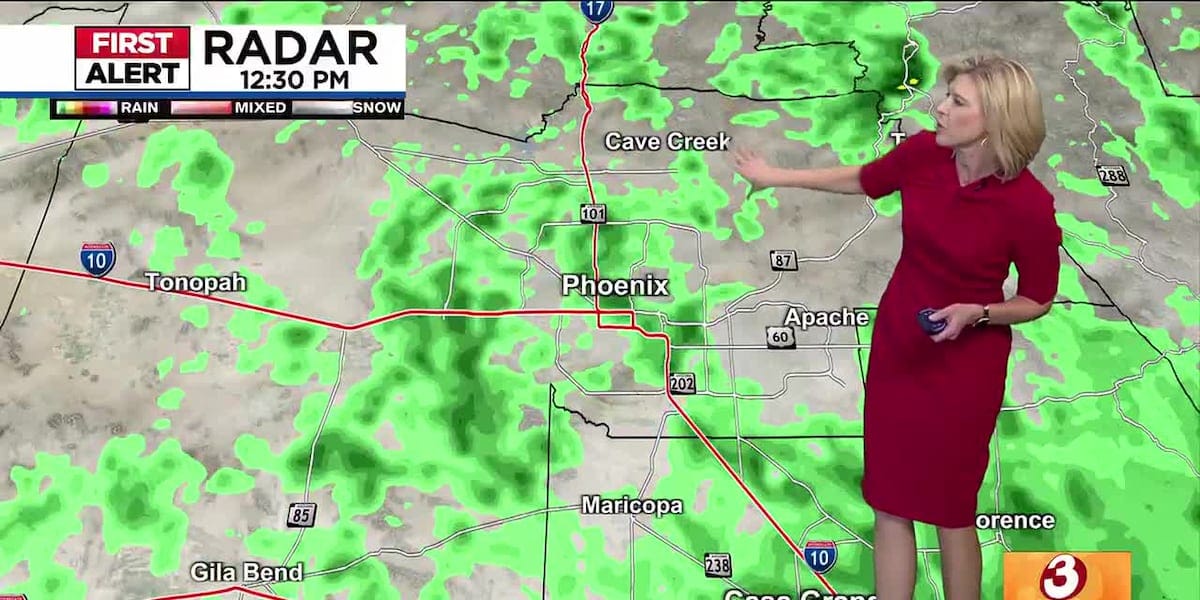

Let’s cut through the sugarcoating that passes for news coverage these days. The headlines are buzzing about Phoenix getting a little bit of rain for Christmas. Oh, what a miracle, right? A festive sprinkle to wash away the sins of the year. The reality, however, is a bitter, cynical joke. The input data tells us Phoenix broke a heat record for the third consecutive day, hitting 80 degrees just before Christmas Eve. Let that sink in: 80 degrees. In December. This isn’t a minor fluctuation; it’s a sign that the climate in the Southwest is fundamentally broken, irreversibly broken, and the media wants us to focus on the “spotty showers” like it’s some kind of salvation.

This isn’t a story about a little rain; it’s a story about denial. It’s a psychological defense mechanism where we focus on the tiny, fleeting positive—the possibility of a slightly cooler Christmas—to avoid facing the terrifying, long-term implications of the record-breaking heat that preceded it. The narrative of “change coming” is a comforting lie, a pie-in-the-sky fantasy designed to soothe the masses who are, frankly, ill-equipped to handle the actual scientific reality of what’s happening. The change isn’t a return to normal; the change is a descent into a new, hotter, drier, and more desperate reality. We are witnessing the slow-motion collapse of a habitable environment, and our response is to cheer for a few drops of rain that do absolutely nothing to alleviate the systemic crisis. It’s a classic case of kicking the can down the road, except now the can is on fire, and we’re just hoping the little bit of moisture helps keep the flames from reaching our front door for another day. This holiday “miracle” isn’t a gift from nature; it’s a cruel taunt from a dying ecosystem.

Question 1: Is this rain really a “change coming” for Phoenix’s weather patterns?

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a change; it’s a statistical anomaly in a downward spiral. The core issue, the elephant in the scorching room, is the record-breaking heat. Phoenix hitting 80 degrees in December is not normal. It’s not part of a natural cycle; it is, quite plainly, a symptom of global climate collapse that is disproportionately affecting arid regions like the American Southwest. A single day, or even a few days, of “spotty showers” does absolutely nothing to reverse a multi-year trend of drought and increasing temperatures. The city relies heavily on snowpack in the distant mountains for its water supply, and these minor, localized precipitation events are inconsequential in the context of large-scale water replenishment for Lake Mead and Lake Powell. The fact that we are celebrating this minuscule amount of rain—a mere inconvenience in a normal winter—highlights how desperately we are grasping for any sign that things aren’t as bad as they seem. It’s a classic psychological operation, where a minor positive event is used to distract from the larger, catastrophic trend. The change coming isn’t a nice, gentle shift back to normalcy; it’s a permanent, brutal readjustment to a climate that is fundamentally hostile to human life.

The Historical Context of Denial

To understand the depth of this denial, you have to look back at the historical context. For decades, scientists have warned about the desertification of the American Southwest. Phoenix, a city built on the premise of endless growth in an inherently unsustainable environment, is now facing the consequences. The Colorado River, the lifeline for this region, is drying up. The snowpack that once reliably fed the river system is diminishing in both volume and duration. When you have three consecutive days of record heat in December, it indicates a fundamental shift in atmospheric conditions. The atmosphere is holding more heat, creating high-pressure domes that trap warm air over the region. This isn’t just about a couple of hot days; it’s about the entire system being rewired. The “rain possible on Christmas Day” is nothing more than a momentary blip, a statistical outlier in a year of continuous and terrifying record-breaking heat. To call this a “change coming” in a positive sense is to completely misunderstand the severity of the situation. It’s like putting a single band-aid on a massive, arterial wound and declaring the patient cured. It’s foolish, and frankly, dangerously misleading.

Question 2: What are the long-term implications of December heat records for the Southwest’s water crisis?

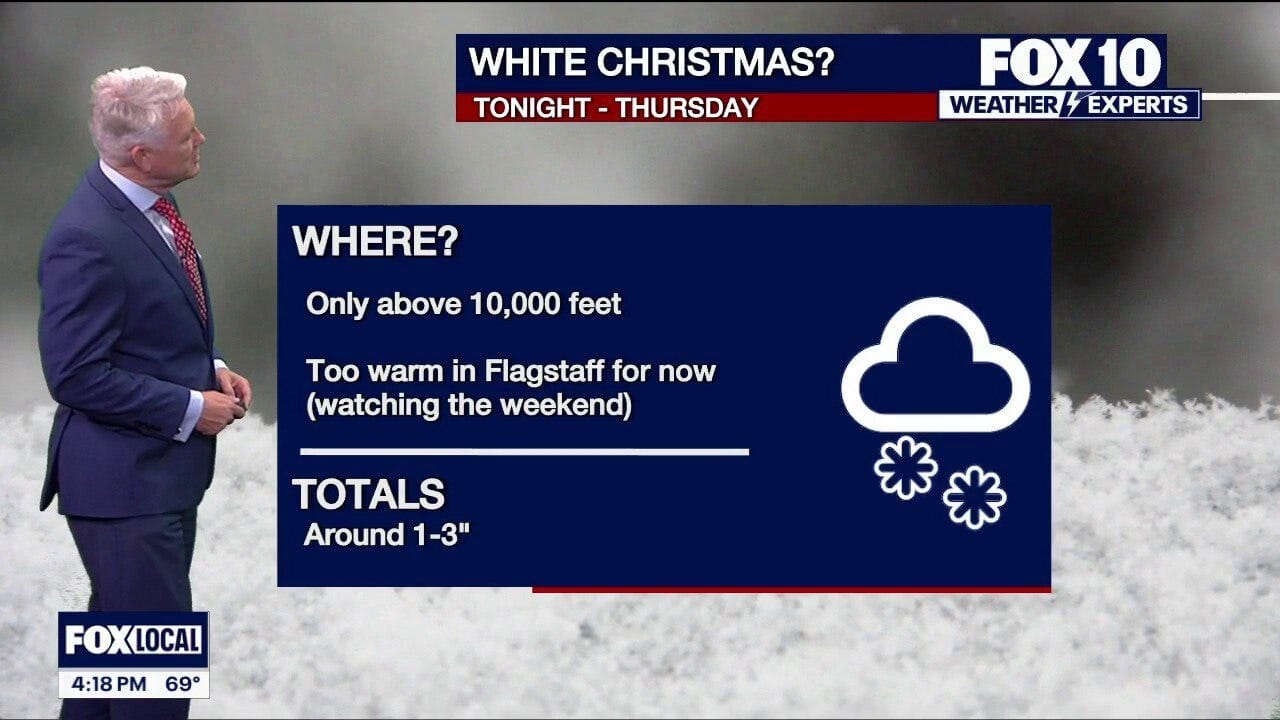

This is where the real story lies, far beyond the superficiality of a holiday forecast. The record-breaking December heat directly impacts the Southwest’s most critical resource: water. The winter months are crucial for building the snowpack in the Rocky Mountains that provides the majority of the water for the Colorado River system, which in turn feeds cities like Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. When you have unseasonably high temperatures, even small amounts of precipitation fall as rain instead of snow. Rain runs off quickly, causing flash floods and evaporating rapidly, while snowpack acts as a slow-release reservoir, melting gradually throughout the spring and summer. The fact that Phoenix is hitting 80 degrees suggests that the larger weather patterns necessary for building a substantial snowpack are fundamentally altered. We are trading long-term water storage for short-term, aesthetically pleasing rain. This isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s an existential threat to the millions of people living in the Southwest. The Colorado River crisis is already at critical levels. Lake Mead and Lake Powell are approaching dead pool status. A few localized showers on Christmas Day do absolutely nothing to alleviate this crisis; in fact, they mask the larger problem by providing a false sense of security. The long-term implication is a future defined by water rationing, agricultural collapse, and potentially, mass migration away from the desert megacities. We are approaching a new normal where winter in Phoenix looks more like summer, and summer in Phoenix looks more like an oven. The celebratory tone around this rain is, therefore, entirely misplaced.

The Inevitable Scorch

The cynical investigator in me sees this as the final stage of denial before a systemic breakdown. When the heat records become so extreme that 80-degree Decembers are common, the infrastructure and resources of the region will simply fail. The power grid, which is already stretched thin during the summer, will face increased demand for cooling during the winter months. The cost of living will skyrocket as water becomes scarce and a premium commodity. The agricultural industry, which sustains much of the economy in the Southwest, will collapse. The human body is only capable of withstanding so much heat for so long. As the baseline temperature rises year over year, the “cool” periods become less cool, and the extreme heat events become more frequent and more intense. The “change coming” isn’t a gentle adjustment; it’s a brutal reckoning. The headlines celebrating “Holiday showers” are a pathetic attempt to avoid discussing the inevitable scorched earth that awaits us all. It’s a sign that we’re more concerned with feeling good about a temporary reprieve than with actually addressing the underlying disaster.

Question 3: How does this localized rain event compare to the scale of the crisis in the Colorado River basin?

It doesn’t. This is where the media’s framing truly becomes insidious. They focus on the hyper-local weather event to create a sense of immediacy and relevance, while ignoring the larger hydrological systems that dictate the viability of the entire region. The Colorado River basin drains over 246,000 square miles, feeding multiple states and millions of people. A “spotty shower” in Phoenix, which might drop a quarter inch of rain on a specific neighborhood, has virtually zero impact on the overall water levels in Lake Mead or Lake Powell. The vast majority of the water supply for Phoenix comes from snowmelt in the distant Rocky Mountains, hundreds of miles away. This rain in Phoenix simply evaporates or runs off into storm drains, doing little more than temporarily dampening the surface. To suggest that this a significant development in the context of the water crisis is a form of weather-washing. It’s designed to make people feel better, to instill a false sense of hope that we might actually be able to pray away the climate crisis, rather than investing in massive infrastructure projects, conservation efforts, or, more realistically, planning for the inevitable decline of human settlement in this region. The scale disparity is enormous; we’re talking about a small cup of water to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool that’s nearly empty. It’s not a solution; it’s a distraction.

The Futility of Localized Hope

The cynicism here isn’t just about being contrary; it’s about recognizing the futility of local optimism in the face of global systemic failure. The climate crisis isn’t something that can be solved by a few localized rain events. It requires massive, structural changes to energy production, consumption patterns, and land use. When a city like Phoenix celebrates a few drops of rain while simultaneously building new, sprawling suburbs that demand even more water, the hypocrisy becomes almost comical. The focus on “Holiday showers” distracts from the deeper truth: the city’s growth model is fundamentally incompatible with the long-term climate projections for the region. The heat records are not a temporary inconvenience; they are a permanent feature of a changing climate. The rain is merely a temporary fluctuation, a brief respite before the inevitable. We are essentially rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic while arguing over whether the ice cubes in our drinks are melting fast enough. The real investigation needs to focus on why we continue to live in a state of denial, celebrating minor victories while ignoring the impending catastrophe that looms large over the Southwest.

Question 4: What does this reaction say about human nature and our ability to cope with long-term threats?

This reaction, the celebration of a few spotty showers, perfectly encapsulates the human failure to deal with long-term, systemic threats. We are hardwired to prioritize immediate, tangible sensations over abstract, future dangers. A rain shower provides immediate relief from the heat; a record-breaking temperature increase over three decades is harder to feel and process. This cognitive bias means we are constantly reacting to symptoms rather than addressing the root causes. We celebrate the rain because it feels good now, even though we know deep down that it doesn’t solve the problem of the 80-degree Decembers or the empty reservoirs. The media, being driven by clicks and attention rather than deep analysis, exploits this cognitive bias. They know a story about “rain possible on Christmas Day” will get more engagement than a grim analysis of hydrological collapse. This is why we are stuck in a cycle of short-term thinking and long-term disaster. The cynical investigator sees this as a fundamental flaw in human decision-making, where we are perfectly willing to trade a secure future for a temporary moment of comfort. The “change coming?” headline isn’t a question from an objective reporter; it’s a plea for reassurance from a populace that knows, on some level, that everything is falling apart. The answer is yes, a change is coming, but it’s not the one you want.

The Final Reckoning

The truth is, we are watching a preview of the end of an era. The Southwest, built on the illusion of limitless resources and technological control over nature, is now facing the harsh reality that nature always wins. The 80-degree days in December are a clear warning that the climate models are accurate, possibly even conservative. The celebratory coverage of a few drops of rain is a pathetic attempt to distract from the inevitable reckoning. The future for Phoenix and similar desert cities is not one of gentle showers and continued growth; it’s one of increasing heat, decreasing water, and mass displacement. This holiday season, while others celebrate a possibility of rain, the cynical investigator sees only the growing shadow of a climate crisis that we are, by all accounts, fundamentally incapable of solving because we refuse to accept its reality. The rain is a distraction; the heat records are the story. Don’t fall for the holiday cheer when the house is on fire.