The Deconstruction of a Fadeout: When Grime Doesn’t Pay

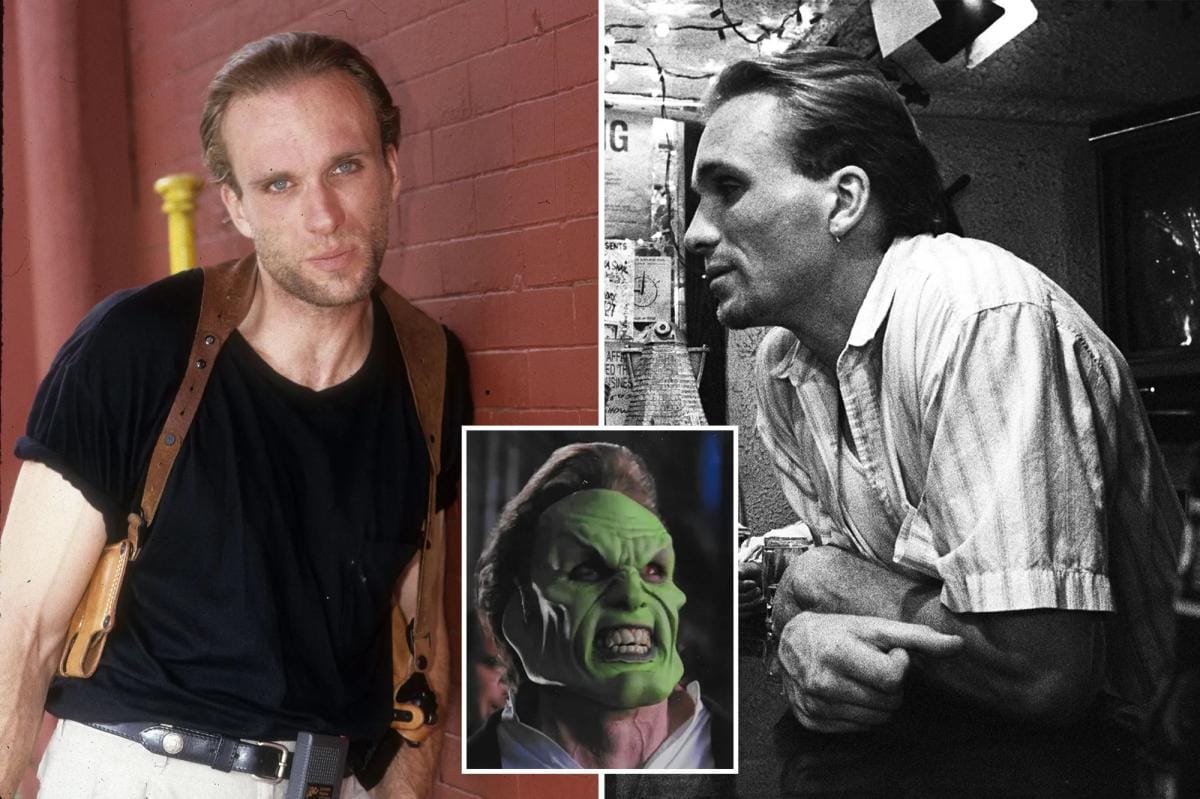

And so, another one bites the dust. It’s a headline that barely registers on the modern media Richter scale: Peter Greene, best known for roles in iconic nineties films like Pulp Fiction and The Mask, found dead at 60 inside his NYC apartment. The news cycle moves on instantly, prioritizing the latest superhero franchise announcement or another manufactured celebrity drama. But if you stop for a second and actually look at the sparse details—found dead at 60—a more insidious story emerges, one that’s far more revealing about the state of modern entertainment than any glossy press release.

Because the logical deconstruction demands we ask why this particular actor, whose face is instantly recognizable to anyone who lived through the last great era of American cinema, ended up here. This isn’t just a statistic; it’s a forensic examination of the industry’s discard pile. Peter Greene wasn’t just ‘that guy from that movie.’ He embodied a specific kind of cinematic menace. He was the quintessential character actor whose talent was rooted in a gritty realism that Hollywood systematically purged over the last two decades. His end, alone in an apartment in New York City at the relatively young age of 60, isn’t just personal tragedy; it’s a metaphor for the industry’s complete devaluation of authentic character work.

The Zed Paradox: The Face of Anomaly in an Era of Homogeneity

Let’s talk about Pulp Fiction. It’s impossible to overstate the impact of Quentin Tarantino’s masterpiece, a film that redefined independent cinema and launched a thousand careers. But while John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, and Uma Thurman became household names, actors like Peter Greene, who provided the film’s truly shocking and visceral edge, were relegated to footnotes. Greene’s character, Zed, in the basement scene, isn’t just a supporting player; he is the personification of the film’s darkest, most uncomfortable themes. He is the physical manifestation of the amorality and random violence that permeated the film’s core narrative, a truly terrifying figure precisely because he lacked the stylized bravado of the hitmen. He was pure, unadulterated sleaze. And that’s exactly why he was so good. Because he wasn’t trying to be cool; he was trying to be genuinely threatening. That kind of performance is a high-wire act, and Greene absolutely nailed it, etching himself into film history with a limited amount of screen time.

But here’s where the paradox kicks in: The very qualities that made him brilliant in that role—the raw, unfiltered intensity, the ability to disappear into a truly repugnant character—are exactly the qualities that make an actor unmarketable in the current environment. Hollywood doesn’t want gritty realism anymore. It wants safe, predictable characters that can be easily packaged and sold across multiple platforms. The modern equivalent of Zed would likely be watered down, given a tragic backstory to justify his actions, and ultimately softened for mass appeal. Greene’s talent was incompatible with this sanitization process.

The Discarding of the Character Actor

Because the industry machine runs on franchises and IP. The focus has shifted from great performances to massive special effects budgets. A character actor’s primary value is their ability to elevate a scene through subtle nuance and powerful emotional depth, but in an era dominated by CGI spectacles, nuance is secondary to spectacle. Greene’s career, post-nineties, reflects this shift. While he worked steadily in independent films and television throughout the 2000s and 2010s, he never achieved the A-list status that many of his contemporaries did. This isn’t necessarily a failure on his part; it’s a failure of the system to utilize talent that doesn’t fit a predetermined mold. The industry essentially told actors like Greene that their unique brand of intensity was no longer needed.

And let’s not forget the other side of the equation: The Mask. A completely different film, a family-friendly comedy where Greene played the primary antagonist, Dorian Tyrell. While less artistically significant than Pulp Fiction, this role demonstrated his versatility. He could be menacing in a cartoonish, over-the-top way when required. But even this role, which gave him mainstream visibility, ultimately didn’t save him from the industry’s eventual culling. Because Hollywood loves to categorize, and once an actor gets labeled as ‘the bad guy,’ it’s nearly impossible to break free from that typecasting, especially when the roles for ‘bad guys’ get shallower and less interesting over time.

The Silence Surrounding the End

But let’s return to the most telling detail of all: found dead at 60 inside his NYC apartment. The logical conclusion here, based on similar high-profile cases of actors who fade from the public eye, is that the industry simply didn’t notice when he stopped working. There was no public battle with a disease, no grand farewell tour. Just silence, followed by a sudden announcement. This is the ultimate betrayal of a character actor: to be used to create an indelible piece of art and then discarded, leaving them to navigate a world that has moved on to flashier, less substantial forms of entertainment. The industry loves to celebrate its stars at award shows, but when the spotlight fades, it rarely provides a safety net or a support structure for those who were essential to its success. This is particularly relevant when considering the demands of Method acting and the emotional toll of playing truly dark characters. It’s hard to imagine that kind of work doesn’t leave scars, scars that are then ignored by a system that only values the next big thing.

And because we live in a culture obsessed with celebrity, we often forget that actors are, first and foremost, human beings. The forensic analysis of his death highlights the brutal reality that a man who helped create one of the most memorable scenes in modern cinema ended up alone. This isn’t a celebration of a life well-lived, but a harsh critique of the industry that failed him. The truth is, Peter Greene’s death didn’t generate the same level of global grief as others because he didn’t fit the current definition of celebrity. He wasn’t on social media constantly, shilling products or engaging in public antics. He was an artist who worked, and when the industry stopped providing opportunities, he faded. This is a pattern we see repeated constantly with character actors from the 80s and 90s, where true grit is replaced by clean-cut appeal.

The Future of Grime: A Bleak Outlook

But the problem extends beyond just Peter Greene. The logical extrapolation suggests that actors like him represent a dying breed. In a world dominated by streaming services, content creation algorithms, and safe, focus-grouped narratives, there is less and less room for true character work. The focus on intellectual property over original storytelling means that roles are often written as templates, not as fully realized human beings. The kind of raw intensity that Greene brought to the screen is often too risky for corporate streamers seeking to appeal to the widest possible audience. They want content that is easily digestible and non-controversial. The grimy underbelly of cinema is being systematically replaced by a sterilized, digital surface. Because of this, we are losing valuable artists who simply don’t fit the new paradigm.

And so, we mark the passing of Peter Greene, not just an actor, but a symptom of a much larger decay. The industry that once celebrated a diverse range of talent now demands conformity. It’s a sad end to a career that promised so much. His death serves as a stark reminder that talent, in itself, is not enough to survive in the entertainment machine. You have to play by the rules, or you get discarded. The silence surrounding his passing speaks volumes. It’s a testament to how quickly we forget the artists who truly define an era. The real tragedy here isn’t just that he died, but that Hollywood let him fade away. The industry’s neglect of a genuinely great character actor is the true story here, far more important than the simple fact of his death at-home death. He was a piece of art, and they threw him away.

Because the logical conclusion is always simple: When you prioritize commerce over creativity, you eventually lose both. Peter Greene’s career trajectory, ending in relative obscurity, demonstrates this perfectly. The gritty antiheroes and terrifying antagonists of the 90s have been replaced by sanitized versions that look good on merchandise. We are poorer for it. And we will continue to continue to lose these artists until we stop treating them as disposable parts of the industry.