The Great Nostalgia Grab: John Stamos and the Algorithmic Content Machine

And so, the machine continues to devour itself, recycling its own parts into an endless, self-sustaining loop designed not for entertainment, but for data aggregation. Because when we talk about John Stamos joining Netflix’s upcoming “The Hunting Wives,” we aren’t talking about a creative choice or artistic vision; we are talking about a calculated move, a cold, hard piece of algorithmic optimization designed to keep us staring at a screen for just one more second, preventing us from ever truly turning off.

But let’s not pretend this is new. The streaming behemoths—Netflix, Prime, Max—they all learned the lesson from Facebook and Google: content is merely a vehicle for data capture. The actual show, be it a high-concept thriller or a reality TV spectacle, is just the bait. John Stamos, the quintessential face of 1990s comfort television, is the perfect hook for this new reality, a familiar face from a time when entertainment felt simpler, more innocent, and less like a targeted psychological experiment. This isn’t a comeback; it’s an acquisition.

The Pre-Digital Past: A World Before Optimization

And yet, we remember the world of Full House, a show so deeply entrenched in the collective psyche of the late 80s and early 90s that its very existence feels like a contradiction to the high-stakes, hyper-sexualized landscape of modern streaming. Because back then, before every viewing habit was logged and analyzed, before every decision was based on focus group results and A/B testing, television was a shared experience. It was a time when a show could simply be popular because it resonated with people, not because it was specifically engineered to exploit a nostalgia gap in the market. The Tanner family wasn’t a product of an algorithm; they were a product of a simpler time when a sitcom about a widower raising three kids with the help of his best friend and his cool brother-in-law felt like genuine comfort food for the masses, not just another piece of intellectual property to be exploited.

But let’s be realistic, that world is long gone. The rise of streaming didn’t just change how we watch television; it fundamentally altered the relationship between the creator and the audience. When Netflix first arrived, it promised freedom—the freedom to watch what you wanted, when you wanted it, free from commercials and schedules. It promised a new golden age of television where complex narratives could thrive outside the constraints of network broadcasting. And for a brief, shining moment, it delivered on that promise, giving us shows like House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black, which felt like genuine artistic leaps forward.

But as these platforms matured, the dark underbelly of the streaming model began to show itself. The data collection, initially used to improve recommendations, quickly became the primary engine for content creation. The algorithm moved from suggesting content to demanding specific kinds of content, favoring endless procedural dramas, low-stakes reality shows, and most importantly, nostalgia reboots. The machine learned that we, as human beings, crave familiarity in an increasingly chaotic world. It learned that bringing back a face like John Stamos, a person who reminds us of a time when the world wasn’t a constant deluge of information and anxiety, is a surefire way to get us to click on a thumbnail.

The Dystopian Present: Casting as a Data Strategy

And so, Stamos joins The Hunting Wives, a show that, based on its premise, sounds like another entry in the ‘suburban dystopia’ genre that Netflix loves so much. Because let’s be honest, the modern streaming narrative often focuses on the breakdown of social structures, the dark secrets beneath pristine surfaces, and the paranoia that infests seemingly idyllic communities. This isn’t just entertainment; it’s a reflection of the anxiety generated by our tech-driven society where everyone is constantly being watched and judged. The show’s premise, a ‘social climber’ and ‘wealthy, manipulative women,’ sounds like a literal dramatization of the dynamics found on Instagram or TikTok, where social validation dictates behavior. It’s a feedback loop: technology causes anxiety, and streaming content reflects that anxiety, keeping us engaged in a cycle of digital dread.

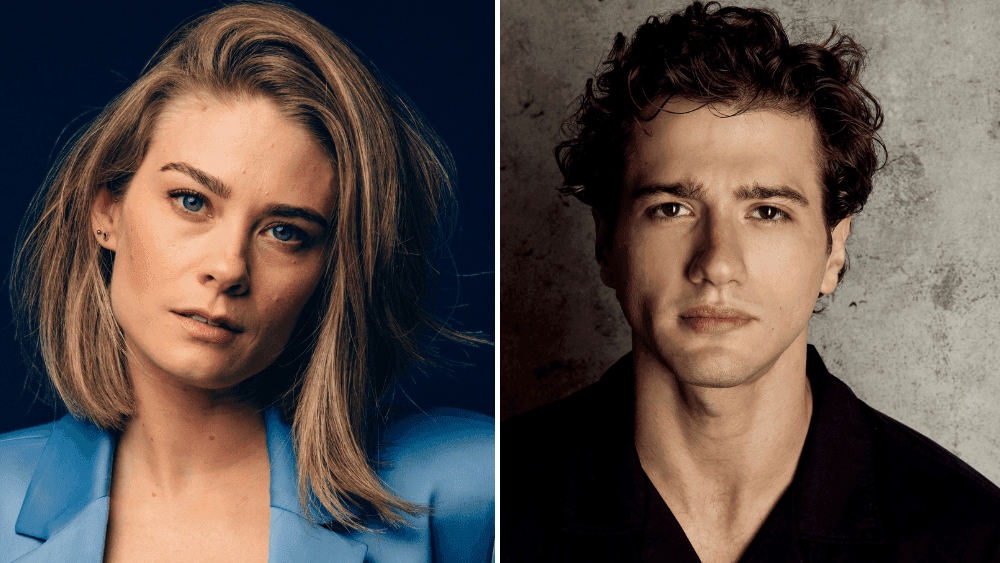

But consider the other castings: Cam Gigandet and Dale Dickey. Gigandet is a solid working actor who fits the mold of a modern leading man—chiseled, recognizable, but not overly expensive. Dickey, on the other hand, is a character actor with immense gravitas, known for her intense, often unsettling performances in independent cinema. The inclusion of these three disparate actors—Stamos (nostalgia), Gigandet (modern standard), Dickey (indie credibility)—is not a creative choice; it’s a demographic targeting strategy. The algorithm is trying to capture three distinct viewing demographics simultaneously. It’s a Frankenstein’s monster of casting, stitched together from different corners of Hollywood to maximize engagement from different corners of the audience pool. This kind of casting, where the actors feel almost interchangeable based on their demographic appeal, is a clear sign that the art of storytelling has been subordinated to the science of data analytics. The individual stories of the characters are secondary to the overall goal of keeping the subscriber count high.

Because let’s not forget the core business model: Netflix needs to constantly acquire new subscribers and minimize churn (the number of people who cancel their subscriptions). Every piece of content, every new show, every new season, is designed with this singular goal in mind. Stamos’s presence isn’t about enriching the show’s narrative; it’s about providing a familiar, bankable name that will appear on a user’s recommendation feed and trigger a memory of a simpler time, prompting a click, prompting a binge-watch, prompting continued subscription payments. The nostalgia factor is a cheap, efficient tool in the streaming wars. It costs far less to acquire a beloved 90s star than it does to develop an entirely original, risky new IP from scratch. The result? A content landscape saturated with reboots, sequels, prequels, and retreads, all designed to make us feel like we’re returning to something comfortable, even as we’re being led further into a digital labyrinth designed to keep us trapped.

And let’s look at the sheer volume of content being produced. The announcement also mentions Kim Matula and Alex FitzAlan joining as recurring guest stars. It’s a constant cycle of adding fresh faces, fresh storylines, fresh bait. This isn’t sustainable for human creativity. It’s a firehose of content designed to overwhelm the viewer, to ensure that there is always something new to watch. The goal isn’t quality; the goal is quantity and constant engagement. The content monster must be fed, and the cost of feeding it is a relentless churning through talent and ideas. The high-burst, high-churn environment of streaming forces creators to make compromises, favoring high-concept premises that look good in a two-minute trailer over nuanced character development. The result is a flood of superficial entertainment designed to provide immediate gratification but leaves us feeling empty afterward, because we’ve been consuming processed digital food rather than actual sustenance.

The Inevitable Outcome: The Dystopian Feedback Loop

But what happens when the nostalgia runs out? When all the 90s stars have been repurposed? When every beloved piece of IP has been rebooted, reimagined, or recycled to death? The dystopian outcome is clear: the algorithm will have exhausted its sources. It will be forced to create new content entirely based on its own data, generating shows that are perfectly optimized for engagement but entirely devoid of soul. We’re already seeing hints of this, with shows that feel like they’re trying to replicate past successes by hitting specific emotional beats or plot points identified by data scientists.

The danger here is not just that we lose good television; the danger is that we lose our ability to discern authentic art from synthetic, algorithmically generated entertainment. The streaming giants are effectively training us to accept less, to crave familiarity over originality, and to mistake constant motion for progress. The casting of John Stamos in a show like The Hunting Wives is merely another step along this path. It’s a sign that the algorithm is now powerful enough to co-opt even the most iconic figures of our pre-digital past, bringing them into its fold to normalize the new reality. It’s a reminder that nothing is sacred in the quest for engagement, and that our memories are just another resource to be mined for profit. The nostalgia is a trap.