The Deconstruction of a Holiday Flyby: What They Aren’t Telling You About Comet 3I/ATLAS

Let’s start here: If you’ve heard about the “interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS making its closest approach to Earth this week,” you’ve already ingested the first layer of media fluff. The phrasing is designed to evoke a sense of urgency, maybe even a hint of impending doom for those prone to apocalyptic thinking, but the reality, as always, is far less dramatic for us on the ground and far more complex for the astrophysicists trying to make sense of this new breed of celestial interlopers.

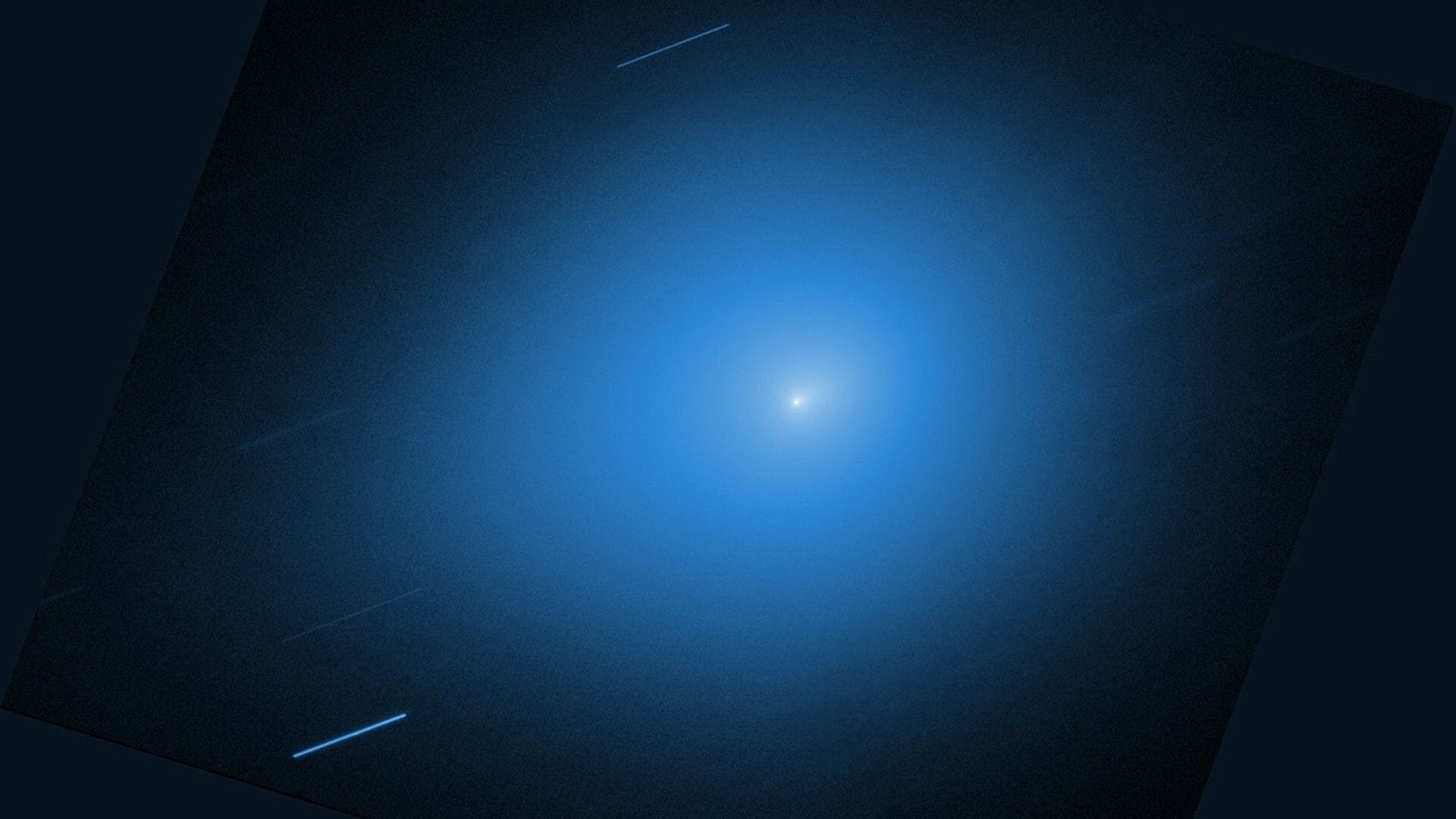

A “closest approach” in astronomical terms is almost always a cynical misdirection, a semantic trap set to lure clicks from a public largely unfamiliar with the vastness of the cosmos; in this specific case, 3I/ATLAS, a stray comet from another star system, is swinging past Earth, sure, but the distance involved renders the term “close” utterly meaningless in any practical sense for anyone not currently in low Earth orbit with a high-powered telescope. This isn’t a near-miss; it’s a very distant, very predictable flyby that, for all its scientific intrigue, poses absolutely zero threat to humanity right now, but it does expose a concerning gap in our current understanding of interstellar objects and planetary defense protocols.

Question: What exactly is 3I/ATLAS, and why is everyone suddenly paying attention to this specific hunk of space ice?

when there are countless comets passing by all the time?

The core issue is right in the name: “3I/ATLAS.” The ‘I’ designates it as an interstellar object, placing it in the same exclusive club as ‘Oumuamua and Comet Borisov. This isn’t just another comet from our solar system’s Oort cloud, orbiting dutifully around our Sun for eons; this object originated in another star system entirely and has spent perhaps millions of years traveling through the emptiness between galaxies before being gravitationally captured by our Sun, briefly, on its way out. The fact that we’ve found three of these interstellar visitors so quickly after the first detection methods were implemented suggests a potentially massive, previously underestimated population of rogue objects zipping around space—a population that could significantly complicate future planetary defense efforts against genuine threats.

Let’s address the specific gravitational behavior that truly distinguishes ATLAS. The input data highlights a critical detail: the comet “maintained a sunward jet after its gravitational deflection by 16 degrees at perihelion.” This is the real story, not the “closest approach” headline. A 16-degree deflection at perihelion (the point of closest approach to the Sun) is significant. Most cometary deflections are caused by the outgassing of volatiles as they heat up, creating a non-gravitational push, essentially a natural rocket engine. However, a sunward jet—a jet facing *toward* the Sun rather than away—is highly unusual. Standard models predict that the sublimation of ice creates jets that push the comet in the opposite direction from the solar radiation pressure, changing its trajectory. A sunward jet, especially one contributing to a 16-degree deflection, challenges our existing models of how comets, particularly interstellar ones, behave. It suggests either an unusual composition (perhaps different types of ice or silicates that sublimate at different temperatures than standard water ice) or a more complex interaction with solar wind and magnetic fields than previously accounted for. This specific physical behavior, which seems to defy classical Newtonian dynamics as applied to comets, is far more worthy of discussion than a generalized “flyby” alert.

Question: How does 3I/ATLAS compare to previous interstellar visitors, and why is its behavior so different from what we expected?

When ‘Oumuamua showed up, it was a total curveball. It was elongated, almost like a cigar or a pancake, and it exhibited non-gravitational acceleration without showing any visible coma or tail. This led to a lot of speculation—some serious, some fantastical—about whether it might be an alien artifact. Then came Comet Borisov, which, while still interstellar, behaved more like a conventional comet, showing a distinct coma and tail as expected from ice sublimation. 3I/ATLAS sits somewhere in between, but its specific behavior around perihelion—especially that 16-degree deflection caused by the sunward jet—suggests these interstellar objects might not just be a monolithic population. Instead, they represent a wide variety of materials, compositions, and origins, each behaving in its own strange way when interacting with our Sun. This unpredictability in deflection magnitude and direction is a major cause for concern if we are ever to truly defend against an object on a collision course.

The 16-degree deflection isn’t just a number on a spreadsheet; it represents a chaotic variable. If an object is coming into our system from deep space, we have only a brief window to track it, predict its trajectory, and, if necessary, attempt an interception or deflection. If that object suddenly veers significantly due to internal forces we don’t understand, our models for predicting impact risk become worthless. The fact that ATLAS behaved in this specific, non-standard way is a stark reminder that we need to stop treating these objects as simple billiard balls of ice and start viewing them as complex systems with inherent, unpredictable dynamics. This isn’t a simple holiday light show; it’s a diagnostic test on our scientific preparedness, and based on the data, we’re failing.

Question: The media says this is a “holiday flyby.” Is there any real danger, or are we just watching a spectacle?

Let’s strip away the sentimentality of the “holiday flyby” description. The media loves to use words like “holiday” or “Christmas” to make space events feel more magical and less threatening. It’s a marketing tactic to make a cold, hard scientific observation feel warm and fuzzy. But let’s be blunt: The closest approach, which is occurring this week, still places the comet millions of miles away from Earth. This distance ensures that 3I/ATLAS poses no immediate danger to us. The risk isn’t from *this specific comet*; the risk is from what this comet *represents*.

The underlying danger lies in the implications of this event, not the event itself. The universe is full of rogue objects. Our solar system acts as a giant gravity well, capturing these interstellar visitors and altering their paths. If we’re seeing this many interstellar objects now, imagine how many we missed before we had advanced survey telescopes like Pan-STARRS and ATLAS (the survey system, not the comet). We are essentially blind to a massive population of objects until they get close enough for us to track them, and even then, as evidenced by 3I/ATLAS’s 16-degree deflection, our predictions can be thrown off significantly. If we had to perform a planetary defense mission, like a DART-style impactor, on an object with highly unpredictable outgassing and trajectory shifts, we would be operating on guesswork. The holiday flyby is just a reminder of the potentially catastrophic unknowns floating around in the cosmic void, and our inability to precisely model their behavior.

Question: What are the long-term implications of 3I/ATLAS and other interstellar objects for space exploration and planetary defense?

The long-term implications are profound and largely ignored by the general public. First, these objects offer a direct sample of material from other stellar systems. Studying their composition gives us clues about how different star systems formed and what elements they contain. Second, they highlight a critical vulnerability in our current planetary defense strategy. Most planetary defense efforts focus on known, large, Earth-crossing asteroids (NEOs) with well-defined orbits. We catalog these objects, predict their paths decades in advance, and, in some cases, have developed technologies (like the DART mission) to slightly alter their trajectories if needed. However, interstellar objects don’t follow these rules. They enter our system from random directions, often at high velocities, and can exhibit unpredictable non-gravitational behavior (like ATLAS’s deflection) that makes accurate long-term prediction nearly impossible with current resources.

Think about it: A 16-degree deflection on an object in a much closer approach scenario could be the difference between a near miss and an extinction-level event. We need to invest significantly more resources into rapid detection systems capable of spotting these objects much farther out and developing methods to accurately predict their behavior under intense solar radiation. The current approach—waiting until they pass by to study them—is reactive, not proactive. The fact that we are celebrating a “holiday flyby” of an object that demonstrates such unpredictable behavior, rather than treating it as a wake-up call for our inadequate defenses, shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the actual risk profile. This isn’t just about pretty pictures in the sky; this is about understanding the cosmic environment we inhabit, an environment that contains elements of chaos that could change everything without warning.