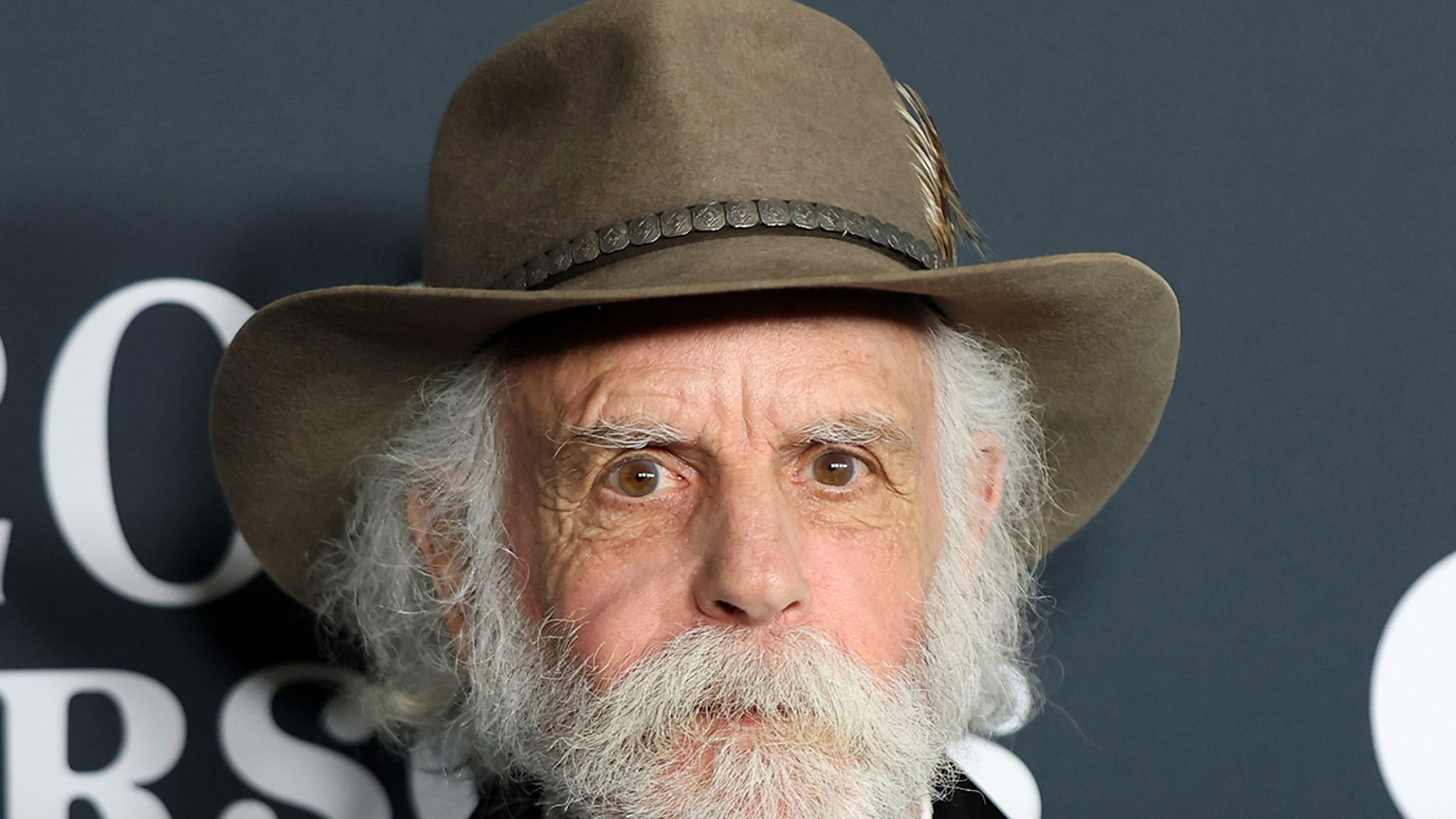

Bob Weir, the influential rhythm guitarist and a founding member of the iconic American rock band the Grateful Dead, has died at the age of 78. His passing marks the end of an era for millions of fans worldwide who revered his distinctive musical contributions and enduring presence in the jam band scene for over half a century.

Weir’s death was confirmed, though further details regarding the circumstances were not immediately available. As a cornerstone of the Grateful Dead, Weir played a pivotal role in shaping the band’s eclectic sound, blending rock, folk, blues, country, and jazz into a genre-defying experience that captivated audiences across generations.

Known for his intricate rhythm guitar work, a dynamic counterpoint to Jerry Garcia’s lead, and his distinctive vocal harmonies, Weir was more than just a band member; he was a vital architect of the Grateful Dead’s improvisational magic and the sprawling musical universe they created. His legacy extends far beyond the band, touching countless musicians and fostering a vibrant community of “Deadheads” that continues to thrive today.

A Founding Pillar of the Grateful Dead

Born Robert Hall Weir on October 16, 1947, in San Francisco, California, Weir’s journey into the heart of rock and roll began in his teenage years. A chance encounter with Jerry Garcia on New Year’s Eve in 1963, when Weir was just 16, proved to be a fateful meeting that would forever alter the landscape of popular music.

This serendipitous meeting led to the formation of Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, which soon morphed into The Warlocks, and ultimately, by 1965, the Grateful Dead. Weir, alongside Garcia, bassist Phil Lesh, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, laid the foundational stones for a band that would defy conventional categorization and establish itself as a cultural phenomenon.

From the outset, Weir’s role was crucial. While Garcia often took the melodic lead, Weir’s rhythm guitar provided the harmonic and rhythmic anchor, often experimenting with complex voicings and unusual chord progressions. This intricate interplay was fundamental to the Grateful Dead’s unique improvisational style, which became their hallmark.

The Architect of Rhythm and Sound

Bob Weir’s approach to rhythm guitar was anything but conventional. Unlike many rhythm guitarists who primarily strum chords, Weir developed a highly fluid and melodic style, often playing arpeggios, inversions, and counter-melodies that enriched the band’s sonic tapestry. His playing was a constant dialogue with Garcia’s lead, Lesh’s bass, and the drumming tandem, contributing to the Grateful Dead’s famously intricate and dynamic sound.

His experimentation with different tunings and his command of diverse musical genres — from blues and country to folk and jazz — allowed the Grateful Dead to seamlessly shift styles within a single song or during expansive improvisational jams. This versatility made him an indispensable component of the band’s sonic architecture, ensuring that their music remained fresh and unpredictable.

Beyond his guitar prowess, Weir was also a significant vocalist and songwriter for the Grateful Dead. He lent his voice to many of the band’s most beloved songs, including “Sugar Magnolia,” “Truckin’,” “Cassidy,” and “Estimated Prophet.” His vocal contributions, often characterized by a distinctive, slightly ragged charm, were integral to the band’s identity, providing a contrasting texture to Garcia’s more melancholic delivery.

Working with lyricists like John Perry Barlow and Robert Hunter, Weir co-wrote numerous tracks that became staples of the Grateful Dead’s live repertoire and studio albums. These songs often explored themes of Americana, wanderlust, and countercultural ideals, cementing his place not just as a musician but as a storyteller within the band.

A Legacy Forged in Improvisation

The Grateful Dead were synonymous with live performance, transforming concerts from mere shows into communal events. Their reputation for extended improvisational jams meant that no two performances were ever truly alike. This commitment to spontaneity and musical exploration created an electric atmosphere that drew legions of dedicated fans, known as “Deadheads,” who often followed the band from city to city.

Weir was at the heart of this improvisational spirit. His ability to react instantly to the musical cues of his bandmates, to shift harmonic landscapes, and to propel the music forward with subtle yet impactful rhythmic variations was key to the Grateful Dead’s legendary live prowess. This democratic approach to music-making, where each member contributed dynamically, set them apart from most rock bands of their era.

Their concerts were not just musical performances but often multi-sensory experiences, featuring elaborate light shows and a relaxed, inclusive vibe. This environment fostered a deep connection between the band and its audience, making the Grateful Dead a pioneering force in what would later be termed the “jam band” genre. Bands like Phish, Dave Matthews Band, and countless others would draw inspiration from the Grateful Dead’s model of extended improvisation and devoted fan engagement.

The band’s tolerance, and even encouragement, of fan-taping at their shows further cemented their unique relationship with their audience and ensured that their ephemeral live performances lived on through countless bootlegs. This revolutionary approach to intellectual property, decades before the internet made such sharing commonplace, speaks volumes about their counter-cultural ethos and commitment to music’s accessibility.

The Enduring Phenomenon of Deadheads

The term “Deadhead” transcends mere fandom; it signifies membership in a unique and enduring subculture. These devoted followers were not just listeners but active participants in the Grateful Dead experience, fostering a sense of community that often felt like an extended family. They traded tapes, shared stories, and celebrated the band’s music with an almost spiritual fervor.

The loyalty of Deadheads is legendary, a testament to the band’s ability to create music that resonated deeply with individuals seeking a sense of belonging and freedom. This devotion is clearly illustrated by the continued proliferation of Grateful Dead culture, even decades after the band’s original lineup ceased performing. For instance, the fact that Massachusetts alone is home to more than four dozen Grateful Dead cover bands highlights the remarkable and sustained appeal of their music.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to specific regions; it’s a global tapestry of tribute bands, fan gatherings, and online communities that keep the Grateful Dead’s music alive and introduce it to new generations. The Grateful Dead, and figures like Bob Weir, didn’t just create songs; they cultivated a movement, a way of life centered around music, improvisation, and communal joy.

Beyond the Grateful Dead: Continued Musical Journeys

The passing of Jerry Garcia in 1995 marked a profound turning point, effectively bringing an end to the original Grateful Dead. However, the surviving members, including Bob Weir, were resolute in continuing to explore the musical landscapes they had helped create. Weir embarked on a series of projects that kept the Grateful Dead’s spirit alive and thriving.

His most notable post-Dead ventures included RatDog, a band formed in the mid-1990s that allowed Weir to further develop his songwriting and guitar playing in a slightly different context, while still drawing heavily from the Grateful Dead’s improvisational ethos. RatDog gained a loyal following, showcasing Weir’s continued artistic vitality and his commitment to live performance.

Later, he reunited with Phil Lesh to form Furthur, a band that explicitly revisited the Grateful Dead catalog while infusing it with new interpretations and extended jams. This project, along with others like Dead & Company (featuring John Mayer), ensured that the Grateful Dead’s music continued to be performed live for massive audiences, introducing their vast repertoire to entirely new generations of fans who never had the chance to see the original lineup.

Weir’s dedication to his craft and his audience never wavered. He remained a constant touring musician, embodying the Grateful Dead’s ethos of continuous musical exploration. Through these projects, he served as a vital link to the band’s storied past, while simultaneously pushing its sound into the future, ensuring its enduring relevance in the contemporary music scene.

A Moment of Reconciliation: The 2001 Stealth Gig

After the Grateful Dead officially disbanded following Jerry Garcia’s death, a period of creative and personal estrangement developed between some of the surviving members. For about three years, the direct musical collaboration between Bob Weir and Phil Lesh, two of the band’s core architects, was limited, a reflection of the difficult transition and differing visions for the future.

It was in 2001 that a significant moment of reconciliation occurred, when Phil Lesh and Bob Weir reconnected for a “stealth gig.” This impromptu, unannounced performance underscored a renewed willingness to collaborate and explore their shared musical heritage. Such events, often occurring in smaller, more intimate settings, became cherished moments for fans, signaling a healing of rifts and a return to the stage together.

This pivotal reunion laid the groundwork for future collaborations, most notably their formation of Furthur, which would become a major touring act celebrating the Grateful Dead’s songbook. The 2001 gig was more than just a performance; it was a symbolic gesture, demonstrating that the profound musical bond between Weir and Lesh, so central to the Grateful Dead’s sound, was resilient and capable of overcoming past differences.

A Timeless Influence on Music and Culture

Bob Weir’s impact, both as an individual artist and as a member of the Grateful Dead, is indelible. The band’s willingness to experiment, their commitment to improvisation, and their unique relationship with their audience reshaped the music industry and inspired countless artists across genres. They proved that commercial success didn’t have to come at the expense of artistic integrity or authenticity.

The Grateful Dead’s music, often infused with themes of freedom, exploration, and community, became a soundtrack to the counterculture movement of the 1960s and beyond. Their influence extends to psychedelic rock, folk-rock, country-rock, and the entire jam band movement, demonstrating a versatility and originality that few bands have ever matched.

Weir’s rhythmic ingenuity and steadfast presence were central to this success. He helped create a musical language that was fluid, complex, and deeply engaging, inviting listeners to become active participants rather than passive observers. His contributions ensured that the Grateful Dead remained a dynamic and evolving entity throughout its existence.

In a landscape increasingly dominated by fleeting trends, the Grateful Dead, championed by musicians like Bob Weir, cultivated a sound and a philosophy that have proven remarkably timeless. Their music continues to be discovered and appreciated by new listeners, affirming its universal appeal and profound artistic merit.

Conclusion

The passing of Bob Weir at 78 leaves a void in the music world, but his legacy as a founding member and driving force behind the Grateful Dead will resonate for generations. He was a master of rhythm, a soulful vocalist, and an innovator whose unique guitar style helped define one of the most beloved and influential bands in history.

Weir’s tireless dedication to his art, his willingness to explore new musical avenues, and his profound connection with fans created a body of work that transcended mere entertainment to become a cultural touchstone. He embodied the spirit of improvisation and community that made the Grateful Dead legendary.

As the music world mourns his loss, the enduring sound of the Grateful Dead, with Bob Weir’s distinctive contributions at its heart, will continue to inspire, entertain, and bring people together, keeping his musical spirit vibrantly alive.