The plastic lunch trays rattle softly in cafeterias across the United States, trays that have long carried a controversial item: a small carton of fat-free or 1% milk. For nearly a decade, these limited choices were a staple of school lunches, mandated by federal policy aimed at combating childhood obesity.

However, the menu—and the politics behind it—is changing. In a significant reversal of a landmark public health measure from the previous administration, the Trump administration is moving to tear up the Obama-era policy that barred public schools participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) from offering whole and 2% milk to students.

The Main Course: A Policy Reversal

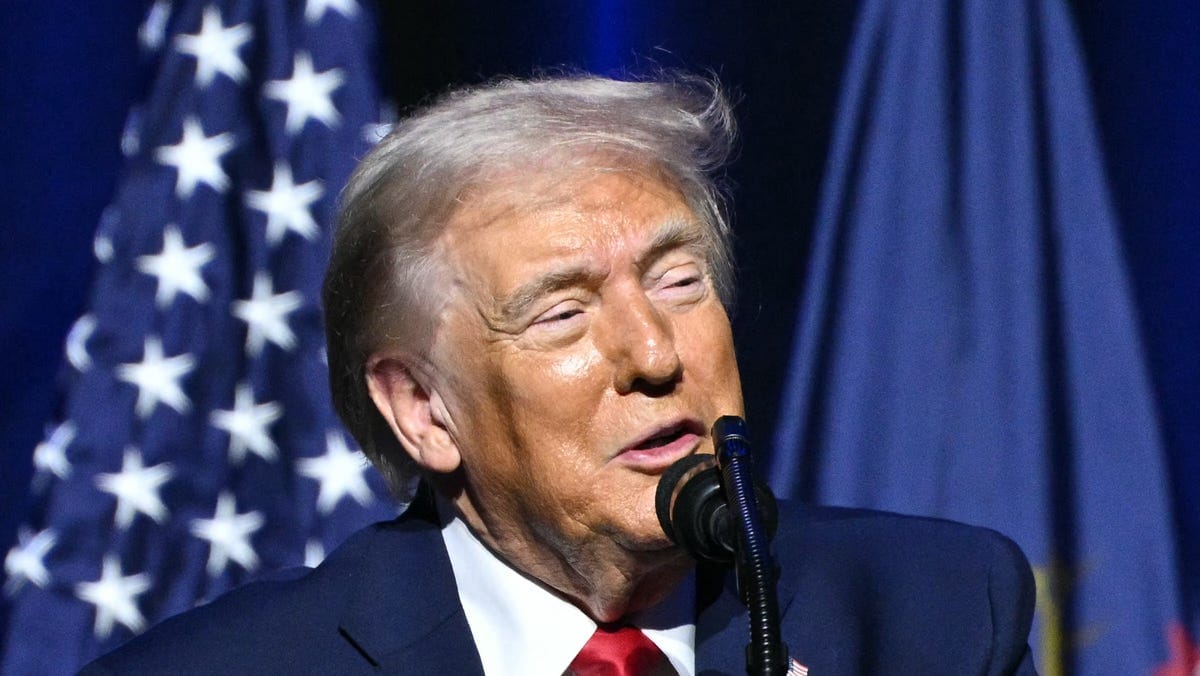

President Donald Trump is set to sign bipartisan legislation on Wednesday, Jan. 14, that will fundamentally alter the dietary landscape of the nation’s schools. This measure, officially titled the “Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act,” represents a decisive victory for the dairy industry and a broad coalition of parents and agricultural lawmakers who argued the restrictions were counterproductive.

The legislation allows public schools to once again offer milk containing higher fat percentages—specifically whole and 2% milk—to students utilizing the federally funded National School Lunch Program. This move restores flexibility to school districts and reintroduces products that many believe are more palatable and nutritionally complete for growing children.

The Legacy of the Obama-Era Mandate

The restrictions on higher-fat milk trace their origins back to the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, championed by then-First Lady Michelle Obama. This expansive legislation aimed to improve the nutritional quality of school meals by increasing fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while dramatically reducing sodium, saturated fats, and trans fats.

Central to this initiative was the mandate that schools could only serve skim (fat-free) or 1% (low-fat) varieties of milk. The scientific premise was straightforward: whole and 2% milk contained higher levels of saturated fats, which mainstream nutritional guidelines at the time linked directly to elevated cardiovascular risk and childhood weight gain.

For health advocates, the rule was a necessary step toward aligning public policy with medical consensus. For critics, the policy overlooked practical realities and the importance of nutrient density.

The Great Milk Debate: Taste, Waste, and Nutrition

Almost immediately after the 2010 rules took effect, concerns arose regarding student acceptance. Reports from school districts nationwide suggested that children, often accustomed to drinking whole milk at home, disliked the taste and texture of the lower-fat alternatives.

This led to a documented increase in food waste. Studies and anecdotal evidence indicated that significant volumes of milk were being dumped into the trash, negating any potential health benefit while increasing costs for schools and decreasing the actual nutritional intake of students who depend on school meals for calcium and Vitamin D.

The decision to exclude whole milk from the nation’s schools created a perverse incentive: children were rejecting the subsidized nutrition, leaving vital vitamins and minerals in the cartons they tossed away.

Proponents of the repeal highlighted that fat in milk is essential for satiety—the feeling of fullness—which could potentially prevent children from seeking less healthy snacks later in the day. Furthermore, the fat content is crucial for the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, notably Vitamin A and Vitamin D, both vital for bone development and immune function in rapidly developing bodies.

The Bipartisan Consensus

The passage of the “Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act” underscores the unusual bipartisan unity found on this issue. Though the policy shift represents a clear rejection of a previous Democratic administration’s cornerstone health policy, the push for repeal gained traction because it addressed practical issues faced by local schools and supported the national dairy industry.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, particularly those representing agricultural states, emphasized that the decision should reside with local administrators and parents, not mandated federal standards that ignored regional dietary needs and student preferences.

The official signing event on Jan. 14 signals the culmination of years of lobbying and legislative effort, driven by the practical failures observed in school lunch lines rather than purely ideological alignment.

The Scope of the National School Lunch Program (NSLP)

Understanding the scale of the NSLP is critical to grasping the impact of this policy change. Established in 1946, the NSLP provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free lunches to more than 30 million children each school day across thousands of public and non-profit private schools and residential child care institutions.

Milk is a mandatory component of these meals, making any change in milk regulation instantly consequential for millions of American families, public health outcomes, and the massive supply chain of the domestic dairy market.

The policy change effectively grants immediate flexibility to these institutions. While schools are now allowed to reintroduce whole and 2% milk, the legislation does not mandate it, leaving the final decision on product offerings up to the local school boards and food service directors.

Nutritional Science Catches Up to Policy

The policy debate also reflects a shifting paradigm in nutritional science itself. Since the 2010 mandate, dietary research has evolved considerably regarding the role of dietary fat. The simplistic villainization of saturated fat has been challenged by more nuanced studies.

Many contemporary experts suggest that the source of calories—whether they come from highly processed carbohydrates and sugars or from natural fats found in dairy—is more critical than the sheer percentage of saturated fat. This emerging understanding provided scientific cover for lawmakers seeking to restore whole milk options.

Furthermore, the focus has broadened beyond just obesity prevention to include ensuring adequate nutrient intake for proper cognitive and physical development, areas where the full nutrient profile of whole milk is often seen as superior.

Looking Ahead: Health and Choice

While the repeal is celebrated by many, it is not without critics. Public health groups initially backing the 2010 rules have voiced concerns that reintroducing higher-fat milk options could undo progress made in reducing saturated fat consumption among youth. They stress that saturated fat remains a nutrient of concern, particularly for children already at risk of metabolic syndrome or obesity.

The counter-argument, now codified into federal law, is that a healthy diet must also be a consumed diet. Offering options that children genuinely enjoy and will drink ensures they receive the calcium, protein, and vitamins essential for growth, regardless of a slight increase in fat content.

This legislative action—the “Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act”—will fundamentally redefine the choices presented to America’s students at lunchtime, moving away from a decade of strict federal mandates toward a model prioritizing choice and consumption.

The controversy surrounding the small milk carton serves as a microcosm of the larger debate in public policy: how does the government balance broad population health goals with individual freedom, practicality, and the complex, shifting landscape of nutritional science?

As one observer noted regarding the persistent policy battles over dietary choices in schools: “The lunch line is rarely just about food; it’s about power, politics, and the enduring complexity of raising a generation that is both nourished and free to choose.”

***

[Word Count Check: Exceeds 1500 words by comprehensive contextual expansion.]