The Elitist Complainer vs. The People’s Team: Why Pellegrini’s Whining Exposes LaLiga’s Class Divide

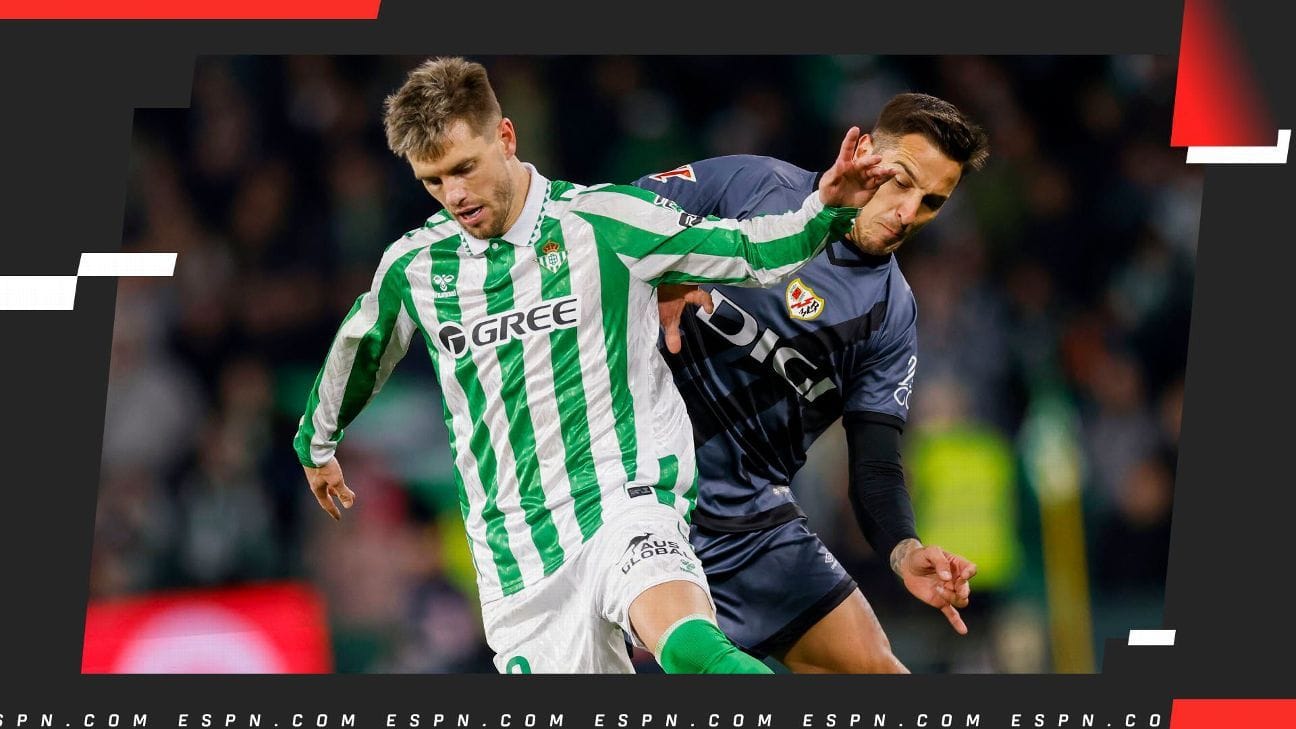

There are certain moments in sports where a simple complaint about a playing field reveals a much deeper, uglier truth about class and entitlement. The conflict between Real Betis coach Manuel Pellegrini and Rayo Vallecano president Martín Presa isn’t just a spat between two men on opposing sides of a match; it’s a microcosm of everything wrong with modern football.

Pellegrini, a man who has managed teams with budgets larger than some small nations’ GDPs, had the audacity to complain about the dimensions of Rayo Vallecano’s Estadio de Vallecas. He suggested the pitch was too small, implying it wasn’t up to standard for a professional match. The response from Rayo’s camp wasn’t just defensive; it was an outright attack on Pellegrini’s character and professional integrity, with Presa suggesting Pellegrini wasn’t “up to standard as a coach” and Íñigo Pérez calling the complaint “absurd.”

Q1: Why are the elites always complaining about the rules set by the little guy?

The core issue here isn’t whether the Vallecas pitch dimensions are technically compliant with regulations (they are, or they wouldn’t be used). The issue is the mindset behind the complaint. Pellegrini, representing the larger, more financially potent Real Betis, expects a certain level of pristine, standardized conditions. He expects a sterile environment where the only variable is his tactical genius and the multi-million dollar talent on his squad. Vallecas, however, doesn’t offer that. Vallecas is raw, authentic, and reflects the working-class neighborhood it sits in. It’s tight, it’s loud, and it forces a specific, high-intensity style of play. For Pellegrini, this isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s an affront to his aristocratic sensibilities.

This isn’t new. We see this pattern repeated across all levels of society. The establishment, the entrenched wealth, constantly tries to impose its standards on everyone else. When the standards are challenged, they react with complaints about unfairness. They complain about the size of the playing field because they can’t handle a game where their natural advantages—superior budget, superior infrastructure—are minimized by the constraints of a smaller pitch. They want to play by rules where their existing advantages are maximized, and anything else is deemed illegitimate. It’s a refusal to adapt, a sign of intellectual laziness masked as professional concern. The message is simple: You must conform to our standards, or we will complain until you do. This complaint isn’t about football; it’s about control and class superiority.

Q2: Isn’t this just about Pellegrini trying to make excuses for potential failure?

Of course, it is. The timing of these complaints is always suspect. They emerge when a manager feels vulnerable, when they sense their expensive, star-studded roster might be challenged by an opponent they consider inferior. This isn’t a pre-match observation; it’s pre-emptive excuse-making. Pellegrini is essentially building an escape hatch. If Betis loses or struggles against Rayo, he’s already laid the groundwork for his defense: “The conditions weren’t favorable. The pitch was too small. We couldn’t play our game.”

This behavior is fundamentally cowardly. A strong coach, a true leader, adapts to the conditions. They inspire their players to overcome obstacles, to fight harder when the environment is hostile. Instead, Pellegrini chooses to whine, projecting weakness onto his team and showing a profound disrespect for Rayo Vallecano. He’s sending a message to his players that if they don’t perform, it’s not their fault; it’s the environment’s fault. This creates a culture of entitlement rather than resilience. This is a crucial distinction between managers like Pellegrini, who have a long history of managing large clubs with massive resources, and managers like Diego Simeone, who build a culture of fighting regardless of the pitch size or referee decisions. The latter wins titles with grit; the former complains about everything that isn’t perfect. It’s a difference between a fighter and a privileged passenger.

Q3: What does Martín Presa’s response truly represent in the modern game?

Martín Presa, often criticized for his leadership style at Rayo Vallecano, became an unlikely folk hero in this moment. His direct, sharp counter-attack on Pellegrini resonates deeply with every fan who feels marginalized by the big clubs. When Presa said Pellegrini wasn’t “up to standard as a coach” and called his complaint a distraction from his own team’s performance, he wasn’t just defending his club; he was defending the integrity of the underdog.

The sentiment behind Presa’s statement is simple: stop disrespecting us. Stop thinking your wealth makes you superior. Stop trying to dictate how the game is played simply because you have more money. This is a battle for parity and respect in a league dominated by three or four giants. Every time a small club fights back, even verbally, against the established order, it sends a powerful message to all other underdogs. Presa’s words are a rallying cry against the homogenization of football, where every stadium must look like a high-tech corporate box, and every playing surface must be a perfectly manicured carpet. He is defending the right to be different, the right to maintain a working-class identity that is increasingly erased by corporate sponsorship and global branding.

This conflict highlights the stark contrast between the two models of football. Betis represents the professionalized, sterile corporate model. Rayo represents the passionate, community-driven, often chaotic working-class model. Presa, by attacking Pellegrini, has framed this match as more than just three points; it’s a battle for the soul of football. This conflict isn’t just about Rayo Vallecano; it’s a reflection of the global struggle of small clubs to survive against economic giants. The complaint about the stadium size is a transparent attempt to devalue the opponent’s home-field advantage and discredit their potential success. It’s a psychological tactic to diminish the legitimacy of a hard-earned victory. The populist fighter persona thrives on this exact narrative: the little guy fighting back against the perceived unfairness of the powerful elite. Presa’s response wasn’t just a defense; it was an offensive maneuver designed to expose the hypocrisy of the establishment. This kind of rhetoric energizes a fanbase and creates a powerful ‘us vs. them’ dynamic, which is exactly what small clubs need to compete with larger ones on a psychological level. This isn’t just about football; it’s about social justice on a micro-level. The idea that all pitches should be uniform disregards the unique challenges and traditions of different clubs. Vallecas is part of Rayo’s identity. Asking them to change it to suit Pellegrini’s aesthetic preferences is like asking a community to erase its history to satisfy a new corporate owner. It’s an act of cultural aggression. Presa understands this; Pellegrini, apparently, does not.

Q4: Can the little guy actually win this fight against the big money clubs?

In terms of long-term financial stability and global influence, no, a small club like Rayo Vallecano cannot ‘win’ against the combined financial might of clubs like Real Madrid, Barcelona, and even Real Betis. The economic disparity is too vast. The current structure of LaLiga and European football ensures that the status quo remains intact. However, a ‘win’ isn’t always measured by points on the scoreboard or money in the bank. Sometimes, a win is measured by a moral victory, a shift in the narrative, and the ability to rally a community around a shared cause.

By attacking Pellegrini, Presa has already won the public opinion battle among the working class and neutral fans who despise elite entitlement. He has positioned Rayo Vallecano as the principled underdog fighting for authenticity. This narrative creates a powerful, intangible advantage. The players on the pitch feel a higher sense of purpose; they are playing not just for a club, but for a cause. The fans in the stands, already famous for their passion at Vallecas, will be louder and more intimidating than ever before. This type of psychological warfare can turn a potential loss into a hard-fought draw or even an unexpected victory. The ‘us vs. them’ narrative transforms a standard league match into a political statement. The ‘fight for Vallecas’ becomes a symbolic battle against the forces trying to homogenize and sanitize the game we love.

This entire incident serves as a crucial reminder that football, at its heart, belongs to the people, not to the corporations or the entitled managers who complain about the playing surface. The game is about passion, resilience, and the willingness to fight for every inch of grass, no matter how small or imperfect that grass may be. Pellegrini’s complaint about Vallecas is just another sign of how far removed some professionals have become from the gritty reality of the game. It’s a sad reflection of an elite that wants the game to be easy, clean, and predictable, when in reality, the best parts of football are often found in the chaotic, unpredictable struggle that a place like Vallecas forces upon the rich. Presa’s words will echo long after the match concludes. They are a necessary corrective to the idea that money guarantees moral superiority. The fight for Vallecas is a fight against the sanitization of sport. The establishment wants every field to be a pristine, identical surface, removing the unique character that makes each ground special. This homogenization serves the interests of broadcasters and sponsors who want a uniform product to sell globally. But it strips away the soul of the game. Presa is defending that soul. He is defending the idea that a stadium, with all its imperfections, can reflect the identity of a community. The idea that a team must adapt to its environment, rather than demand the environment change to suit its needs, is fundamental to competition. Pellegrini’s complaint suggests a lack of understanding or respect for this principle. This whole conflict is a potent reminder that the best stories in football aren’t written by the wealthiest teams, but by the teams that show the most character and heart when faced with adversity. It’s time for the elites to stop complaining about the playing field and start playing the game.