The Anatomy of a Thirty-Year Echo

Let us not be fooled by the romance of it all. The narrative being spun is one of artistic destiny, of characters so beloved they demanded a return, of a filmmaker finally revisiting the lightning strike that launched his career. It’s a lovely story. It is also, from a strategic perspective, almost entirely a fabrication designed for marketing copy. The return of the McMullen clan in ‘The Family McMullen’ after a thirty-year sabbatical is not a miracle of creative inspiration; it is a calculated, almost brutally logical, move in a media ecosystem that feasts on the bones of past successes. It is the weaponization of nostalgia, executed by a creator who understands the modern content battlefield better than most.

1995: An Anomaly in the System

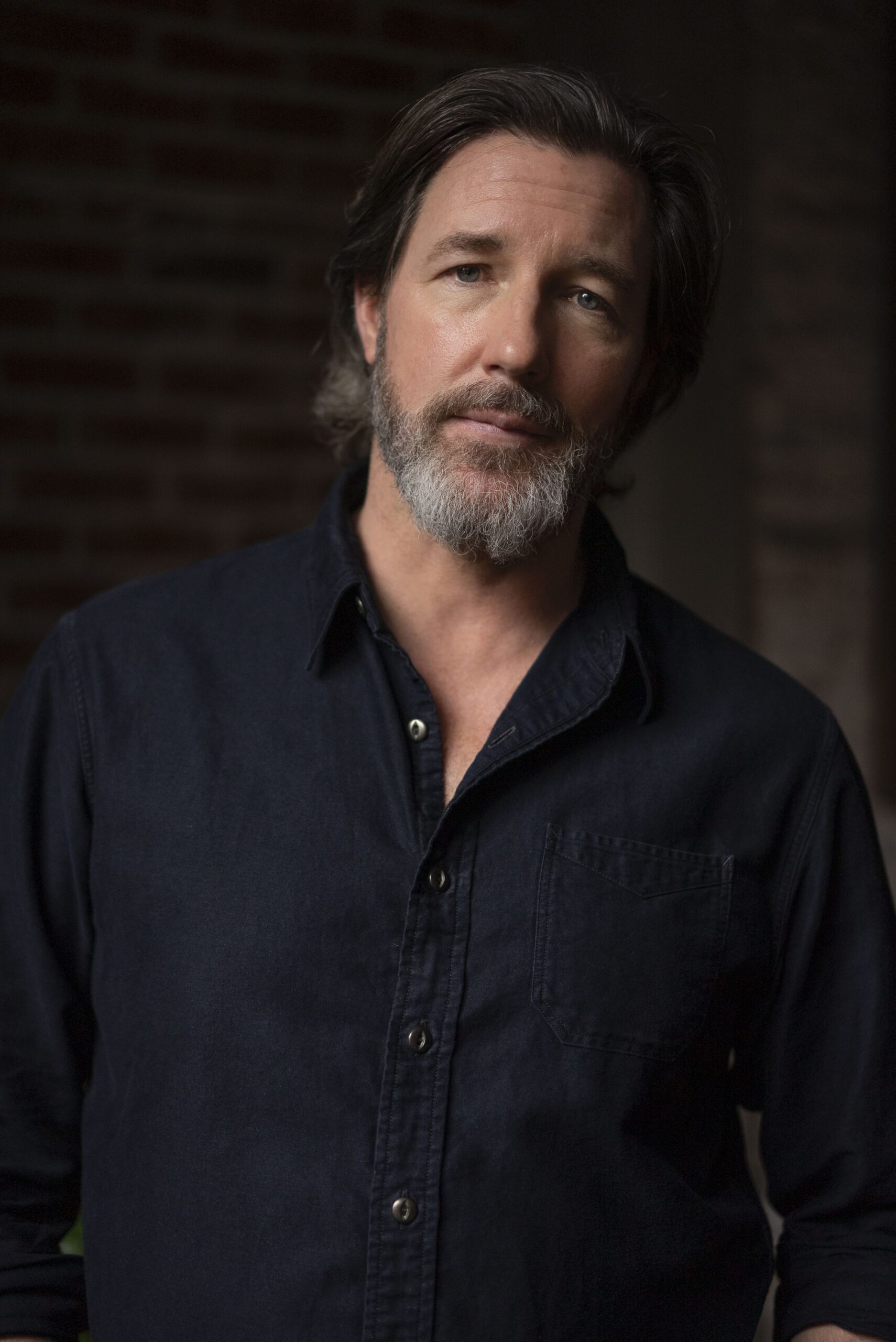

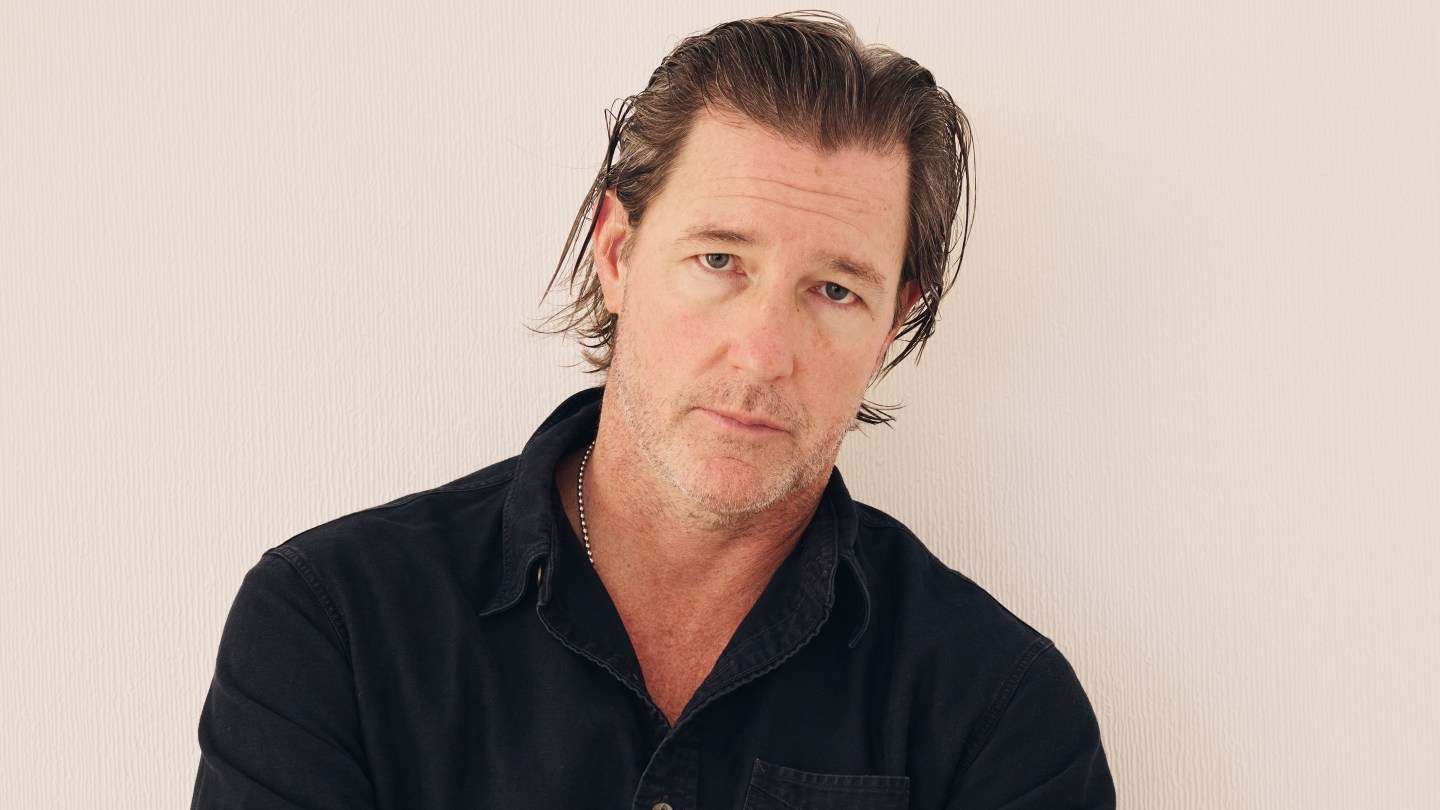

To understand the ‘why now,’ one must first dissect the ‘what then.’ 1995 was a different universe. The Sundance Film Festival wasn’t the corporate-sponsored, celebrity-saturated bazaar it is today; it was a genuine frontier for discovery. Edward Burns, with ‘The Brothers McMullen,’ became the poster child for a dream that was, even then, starting to fade: the no-budget auteur. He famously shot the film on weekends for a pittance (the legend says around $25,000), using his parents’ house as a set and cajoling friends and family into service. It was a raw, talky, deeply unpolished look at the romantic entanglements and Catholic guilt of three Irish-American brothers on Long Island. It felt real. It felt attainable. He didn’t just make a movie; he created a business model that thousands of aspiring filmmakers would try, and fail, to replicate.

But lightning, by its very nature, rarely strikes twice. The success of ‘The Brothers McMullen’ was a perfect storm of timing, narrative, and a market starved for authenticity. It was an anomaly. Burns became ‘Ed Burns, the indie film guy,’ a brand he has cultivated (and been trapped by) ever since. His subsequent career has been one of admirable consistency and workmanlike effort, but it has never recaptured the seismic shock of his debut. He made other films, good films even, but they existed in the long shadow of that first, miraculous success. He became a reliable character actor, a director of modest, personal projects. Meanwhile, his co-star, Connie Britton (the luminous Molly McMullen), saw her career take a completely different trajectory, ascending to television royalty with hits like ‘Friday Night Lights’ and ‘The White Lotus.’ Their paths diverged, representing two different outcomes of that initial Sundance explosion: one a steady, controlled burn, the other a slow-building supernova.

The Cold Calculus of the Comeback

So, after three decades of moving forward, why look back? The answer is not in the heart, but on the balance sheet. We are living in the age of the IP (Intellectual Property). Streamings services and studios are not in the business of risk; they are in the business of recognizable assets. A new, original idea from Ed Burns in 2024 is a gamble. ‘The Family McMullen,’ however, is not a new idea. It is a pre-existing asset with a built-in audience, a legacy brand name, and a powerful, marketable hook: the 30-year reunion. It’s a low-risk, high-reward proposition for any platform looking to capture the eyeballs of Generation X and older millennials who remember the original with fondness. It’s a content play. Plain and simple.

The thirty-year mark is not an arbitrary number. It’s a generational milestone. It provides the perfect temporal distance for nostalgia to metastasize from simple memory into a potent emotional longing for a ‘simpler time.’ The characters aren’t just older; they are vessels for the audience’s own aging process. What happened to Jack’s marriage? Did Barry ever find himself? These questions are proxies for our own life audits. Burns isn’t just selling a movie; he is selling a form of cinematic therapy, a chance for an entire demographic to check in with their younger selves through the lens of these fictional characters. This is a far more powerful and bankable commodity than a simple film narrative. It’s brilliant, really. He waited long enough for the property to accrue immense nostalgic value, and now he is cashing in the chips. This isn’t a filmmaker needing to tell a story; this is a strategist liquidating a long-held asset.

The Inherent Danger of Unearthing the Past

The strategic brilliance, however, does not mitigate the immense artistic risk. The original film worked precisely because of its flaws and its context. It was a shoestring, dialogue-heavy indie from the 90s. That was its charm. Can that same energy be replicated today with better cameras, bigger budgets (however modest), and actors who are now seasoned veterans? The danger is that in polishing the form, you kill the spirit. What was once charmingly amateurish could now look clumsy. What was once refreshingly honest could now feel like a hollow echo. The world that made the McMullens relevant—a pre-internet, pre-social media landscape where conversations happened in living rooms, not in comment threads—is gone. It cannot be brought back. Trying to recapture it risks creating a pastiche, a museum piece that reminds us of something we once loved but can no longer feel.

And what of the happy ending? The original film famously tied everything up in a neat bow, a choice Burns himself has expressed some regret over, attributing it to the influence of films like ‘Moonstruck.’ Revisiting these characters means either honoring those neat bows (which could feel static and dramatically inert) or undoing them entirely. If Molly and Jack’s marriage fell apart after all, doesn’t that cheapen the emotional climax of the first film? If the brothers are still wrestling with the same essential problems thirty years later, isn’t that just… depressing? The tightrope walk is perilous. The sequel must simultaneously honor the memory of the original while justifying its own existence with new conflict and growth. It’s a task that has sunk countless legacy sequels before it. The very act of making this film puts the legacy of the first one on the line. It’s a hell of a gamble, strategically sound on paper, but artistically fraught with the potential for disaster. The market may reward the attempt, but history judges the result.