Deconstructing the Artifact

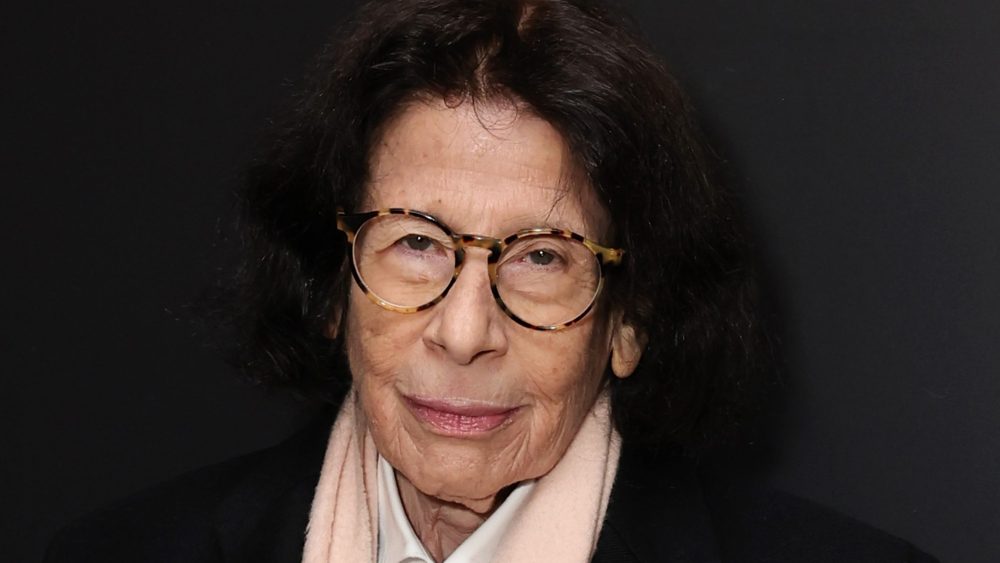

To understand Fran Lebowitz, you must first dispense with the notion that you are engaging with a contemporary writer or a public intellectual in the traditional sense. You are not. Because what you are actually observing is a meticulously preserved cultural artifact, a walking, talking museum piece from a version of New York City that exists more powerfully in memory and myth than it ever did in reality. And her entire public-facing persona, from her disdain for technology to her complaints about tourists during the holidays, isn’t a series of organic opinions. It’s a product. A brand. A very, very successful one.

Her system is brilliantly simple. It is predicated on a single, unwavering axiom: everything new is inherently worse than what it replaced. It’s a philosophy that requires zero intellectual heavy lifting but provides maximum return in the form of knowing nods from an audience desperate to feel superior to the vulgarity of the present. Easy. But this isn’t wit; it’s a formula. And when we apply a forensic lens to her catalog of grievances—gleaned from her rare interviews and public pronouncements—we see not a sharp-tongued flaneur, but a master of brand management whose primary output is the performance of discontent.

The Operating System of Annoyance

The core programming of the Lebowitz persona runs on a few key subroutines. First, there’s the Urban Decay Complaint Module, which activates whenever topics like New York City, especially during peak seasons like the holidays, are mentioned. Her commentary isn’t a nuanced take on urban planning or socio-economic shifts; it’s the lament of a monarch surveying a kingdom overrun by peasants. The tourists, the commercialization, the sheer chaos—these are not problems to be solved but aesthetic affronts to her personal sensibilities. She talks about ornaments made in her likeness without her permission, a perfect encapsulation of her worldview: her very image, like the city itself, has been co-opted and cheapened by the masses she disdains. It’s not about the ornament; it’s about the loss of control over her own curated world.

And this is where the logical disconnect begins to show. Because the New York she pines for, the gritty, authentic, pre-tourist Eden, was also a city of rampant crime, economic collapse, and urban decay that made it unlivable for millions. Her nostalgia is selective. It’s a curated memory, polished and sold as wisdom. She mourns the loss of a city that has, by all objective measures, become safer, cleaner, and more prosperous, precisely because that prosperity brought in the very people she finds so tiresome. She wants the aesthetic of the 1970s with the property values and safety of the 2020s. You can’t have both.

The Luddite Fallacy: From Leaf Blowers to AI

Then we have the Technological Rejection subroutine, a cornerstone of her brand. The input data mentions her visceral hatred for leaf blowers, calling them a “horrible, horrible invention.” This seems like a trivial, harmless complaint. A quirk. But it isn’t. It’s a microcosm of her entire intellectual framework. Analyze the objection: a leaf blower is noisy and disruptive. But it is also a tool of efficiency, replacing the manual labor of a rake. Her objection is not rooted in a logical critique of its environmental impact or sound pollution regulations; it is an emotional, aesthetic rejection of a modern convenience that disrupts her peace. The problem isn’t the machine; the problem is that the world has failed to arrange itself around her personal comfort.

Now, extrapolate this exact logic to her widely publicized views on more complex technologies. Driverless cars. Artificial Intelligence. Smartphones. Her arguments against them follow the exact same pattern as her leaf blower complaint. She doesn’t engage with the nuanced ethical debates surrounding AI alignment or the socio-economic impact of automation. Instead, she offers blanket dismissals based on personal inconvenience or a gut feeling of distrust. She’s famous for not owning a computer, a phone, or even a typewriter, a fact presented as a badge of honor, a sign of intellectual purity. But it is the opposite. It is a willful ignorance, a deliberate choice not to understand the world as it currently operates. Refusing to learn how a smartphone works isn’t a brave intellectual stance; it’s the adult equivalent of a child putting their hands over their ears and humming loudly. Her critique of AI is meaningless because she has preemptively disqualified herself from the conversation by refusing to engage with the foundational technology of the last forty years. It’s like a food critic refusing to taste anything seasoned with salt.

The Performance of Intellect

The difficulty in contacting her, requiring “three intermediaries” for a simple interview request, is not the charming eccentricity of a reclusive genius. It is the carefully managed access control of a luxury brand. Brands are defined by scarcity and mystique. By making herself inaccessible, she elevates her status from a mere commentator to an oracle. One must make a pilgrimage. It’s pure theater, designed to reinforce the idea that her time and her thoughts are immensely valuable. But what is the actual substance of those thoughts?

The Emptiness of the Throne

Consider her pronouncements on broader topics. When she says, “hiking is the most stupid thing I could ever imagine,” she is not making a serious point. She is reinforcing the brand. The brand is Urban. The brand is Indoors. The brand does not sweat. The brand finds nature tedious. Any activity that falls outside these parameters is therefore “stupid.” This isn’t an argument; it’s a content filter. It’s the same cognitive reflex that dismisses driverless cars without consideration. It is a profound lack of curiosity disguised as discerning taste.

And this is the core of the Lebowitz myth. She is celebrated as a great writer who famously suffers from “writer’s block.” But after decades, one has to question the diagnosis. Perhaps it isn’t a block. Perhaps, after her initial success with *Metropolitan Life* and *Social Studies*, she discovered that it was far easier and more lucrative to *play the part* of a writer than to actually do the grueling, solitary work of writing. The talk show circuit, the speaking engagements, the Netflix documentaries—they all trade on the *memory* of her as a writer. But her current occupation is not writing; it is being Fran Lebowitz. She has become her own greatest subject, and her primary literary output is the endless, unwritten book of her own opinions, delivered verbally and with a world-weary sigh.

So when you watch her hold court, dismantling everything from modern art to political figures like Zohran Mamdani, you are not witnessing a spontaneous burst of insight. You are watching a performer deliver her lines. The script is predictable because the brand must be consistent. Technology bad. Modernity vulgar. New York not what it used to be. Tourists annoying. Comfort paramount. The product is consistent, reliable, and utterly devoid of any new ideas. It doesn’t challenge the audience; it comforts them, assuring them that their own vague anxieties about a changing world are, in fact, signs of a superior intellect. It’s the most brilliant grift of all: selling curated complaint as high-minded philosophy.